Patient Presentation

Helsinki, or Mirko Dragic, is a Serbian mercenary who is a member of the highly specialized team assembled by The Professor for the complex Bank of Spain heist. Before the heist could be completed, an elite military unit was sent in to put an end to the elaborate operation. The unit detonates explosives on the roof to enter the bank. Helsinki is thrown to the ground by the force of the blast and a large marble statue weighing at least two tons crashes onto him, crushing his right leg. Relaying what has just happened by radio, Helsinki states his wound is open, with active exsanguination of blood. With overhead gunfire from the incoming assault team, it takes several minutes before his teammates can come to his aid.

Physical Exam

On examination, you find Helsinki with laboured respirations and skin covered in soot from the explosion, making assessment of skin colour challenging. He is alert and oriented, speaking in full sentences. His leg is impinged under the large statue, just proximal to the right knee. There is a large open wound proximal to the site of impingement with bleed seeping out of it. The femoral pulse is weak, and distal pulses in the right foot are absent. The surrounding combat makes it difficult to assess injury to underlying structures. Helsinki becomes increasingly confused but continues to respond to commands (Glasgow Coma Scale score 13 – E3V4M6).

Discussion

Several members of the crew provide cover fire to allow Palermo and Rio to retrieve a nearby fallen beam and use it as a lever to remove the statue pinning Helsinki’s leg. The total elapsed time since his leg was crushed is difficult to ascertain but can be assumed to be 5-30 minutes given the events that transpired while his leg was trapped.

Crush injuries are a result of physical trauma or prolonged forces acting on various areas of the body. Deleterious consequences of crush injuries can be a result of the initial inciting traumatic force, or the effects caused by the release of chemicals related to tissue ischemia and revascularization.1,2

As in Helsinki’s case, crush injuries can be life-threatening. Systemic complications with organ dysfunction, termed crush syndrome, often result from significant crush injuries.3 Additionally, entrapment of the limbs can result in increased pressure within fascial compartments due to tissue edema and bleeding in the area. This can result in compartment syndrome which causes permanent damage to underlying tissue and even death if not treated.4–6 In this review, we will focus our discussion of crush injuries on the complications of crush syndrome and compartment syndrome.

What is Crush Syndrome? Why Should We Care?

One of the feared complications of crush injuries is crush syndrome, which has a mortality rate as high as 20%.1 There are multiple mechanisms by which muscle cells are damaged in crush injuries.7 Direct damage of myocytes can occur from the inciting trauma, such as a large object falling onto your leg as in Helsinki’s case. Secondly, deprivation of blood flow to the tissue due to swelling results in ischemia and eventual necrosis of cells. Ultimately, the lysis of cells leads to the release of various metabolites such as potassium, phosphorus, and myoglobin.2 When reperfusion occurs after extrication, these compounds are released back into the general circulation and can result in severe metabolic derangements and multiorgan failure.8

The most notable organ at risk is the kidney, although other complications that may arise are acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), pulmonary edema, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and congestive heart failure.1,2,7,8 The acute kidney injury seen in crush syndrome is thought to be multifactorial, with both a direct nephrotoxic effect of heme and myoglobin released in the process of traumatic rhabdomyolysis, and a prerenal component from hypovolemia and hypotension.7

Dysrhythmia due to rapid onset hyperkalemia is the most notable immediate life-threatening complication of crush syndrome, and should be expected even without ECG or laboratory evidence.1,9Early initiation of fluid resuscitation is the mainstay of treatment to prevent crush-related acute kidney injury (AKI).8 As described in their article on the management of crush victims in mass disasters, Sever and colleagues (2012) recommend the administration of 3-6 litres of fluid overall at a rate of 1 L/hr while monitoring urine output and adjusting the rate as necessary to avoid fluid overload.8 After this period of fluid administration, they recommend individualizing the approach based on current urine output, patient volume status, and other environmental and logistic factors. Other interventions that may be utilized include potassium shifting treatments, sodium bicarbonate infusion, and hemodialysis.1

Figure 1. Algorithm for fluid resuscitation to prevent crush-related AKI in patients from mass disasters.8

*Medical signs and symptoms including urine output, age, preexisting health conditions, environmental factors

**Actual fluid amount given depends on the extent of injuries, BMI, urine production, age, and estimated total fluid losses.

Compartment Syndrome

Another complication we must consider in Helsinki is compartment syndrome.

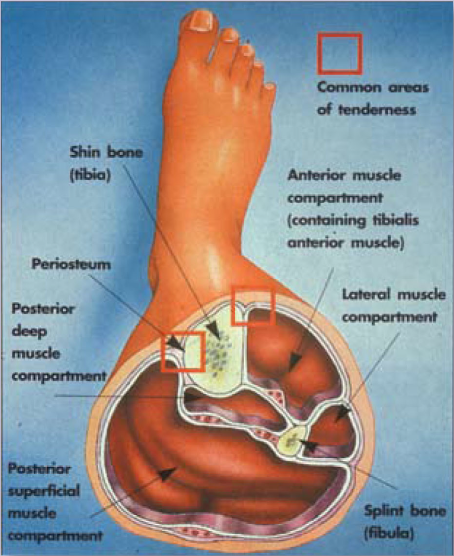

The lower leg is comprised of four compartments, the anterior, lateral, posterior superficial, and posterior deep.10,11 When injury occurs, bleeding and edema can result in increased pressures within these compartments that are bound by unyielding fascial boundaries.4,6 In the later stages of this process, this results in the classic symptoms of acute compartment syndrome (ACS): pain, paresthesia, paresis, and pulselessness.11

In addition to considering the signs and symptoms above, ACS can be diagnosed by measuring intercompartmental pressure. When the intercompartmental pressure exceeds the diastolic blood pressure (DBP), blood flow to the compartment is reduced. One pressure value has not been accepted as a metric for diagnosis of ACS, but consensus within the literature is that when the DBP and intercompartmental pressure differ by less than 30 mmHg, treatment with fasciotomy is indicated.10,12

Fasciotomy is the treatment of choice for ACS. For the lower leg, all four compartments are completely released. A single lateral incision can be used to access and release the compartments, although there is also a two-incision technique.11 Early fasciotomy should be done when ACS is suspected, as early intervention has been shown to reduce long-term complications such as amputation.13

Figure 2. Cross-section of the leg, showing the four compartments. (Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/sportex/3425850575)

Helsinki’s Case

Unfortunately, many of the therapies and interventions we would like to start in Helsinki’s case are not available inside the Bank of Spain during a major heist. After he was removed from the scene of the accident, the only treatment the team was able to provide was intramuscular morphine and splinting of his injured leg.

Ultimately, a negotiation was made with the outside forces to bring in two surgeons to treat Helsinki and one of the soldiers from the opposing force. In an ideal world, they would bring with them supplies for fluid resuscitation, hyperkalemia management, and pain control for initial management. Ultimately, Helsinki will require extensive workup in a hospital setting to assess the extent of metabolic derangement and underlying orthopedic injuries with the likely need for surgery before being released to join his fellow comrades and enjoy the bounty of his efforts.

This post was copy-edited by Noaah Reaume.