Case:

[bg_faq_start] A 51-year-old woman presents to the ED with the chief complaint of left leg swelling. She recently underwent bunion correction surgery to her left foot 7 weeks ago, and her cast was removed one week ago. Over the last day or two she has had significantly increased leg swelling and more recently reports some dull pain described as” heaviness” to the affected leg. The patient denies chest pain, shortness of breath, or cough. On physical examination, her respiratory exam is unremarkable, and her left leg is 2.5 cm greater in circumference than her right, with mild pitting edema in the left leg only. The edema does not encompass the entire left leg. There is no tenderness to palpation of the popliteal fossa or medial thigh and there are no visibly engorged collaterals veins. The patient’s past medical history includes well-controlled hypertension but she is otherwise healthy. The patient is anxious to be treated for her symptoms before leaving for Florida in 5 days for the winter. She remembers being told about the risk of “blood clots” before her surgery and wonders if this is causing her calf discomfort. When the possibility of an ultrasound examination of the leg is brought up, she asks if they will look for clots all the way down to her foot, since that’s where her surgery was. [bg_faq_end]Clinical Question:

[bg_faq_start]Should we be doing whole-leg ultrasounds to look for isolated distal DVTs (IDDVT), and if we find them, how should we manage them?

Isolated distal DVTs are a controversial clinical entity. The distinction between proximal and distal DVTs is usually made at the level of the trifurcation of the popliteal vein, located at or just below the popliteal fossa.1 While there’s a robust literature and consensus around diagnosing and treating proximal DVTs to reduce the risk of pulmonary embolism, recurrence, and clot extension, the evidence around IDDVT is much murkier. Major guidelines differ significantly in management suggestions, and the objective of this article is to discuss some of the controversies and approaches to IDDVT management. The most commonly used guideline for VTE diagnosis and management in North America is the American Academy of Chest Physicians antithrombotic guidelines, which most recently published recommendations about IDDVT in 2012 and 2016.23 On the other side of the Atlantic, the UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines of 2012 and 2015 are more commonly used.45 Let’s consider how each of these guidelines would inform our management of this case regarding a possible diagnosis of isolated distal DVT.

[bg_faq_end]NICE Guidelines:

Both sets of guidelines suggest using the Wells score as the initial step in estimating the pre-test probability from information retrieved from the history and physical. If you want a quick refresher on the Wells score, MDCalc has a good one.6 Beyond the initial step, the guidelines diverge. The NICE guidelines from the UK use a 2-category (high or low risk) Wells score to estimate pre-test probability.

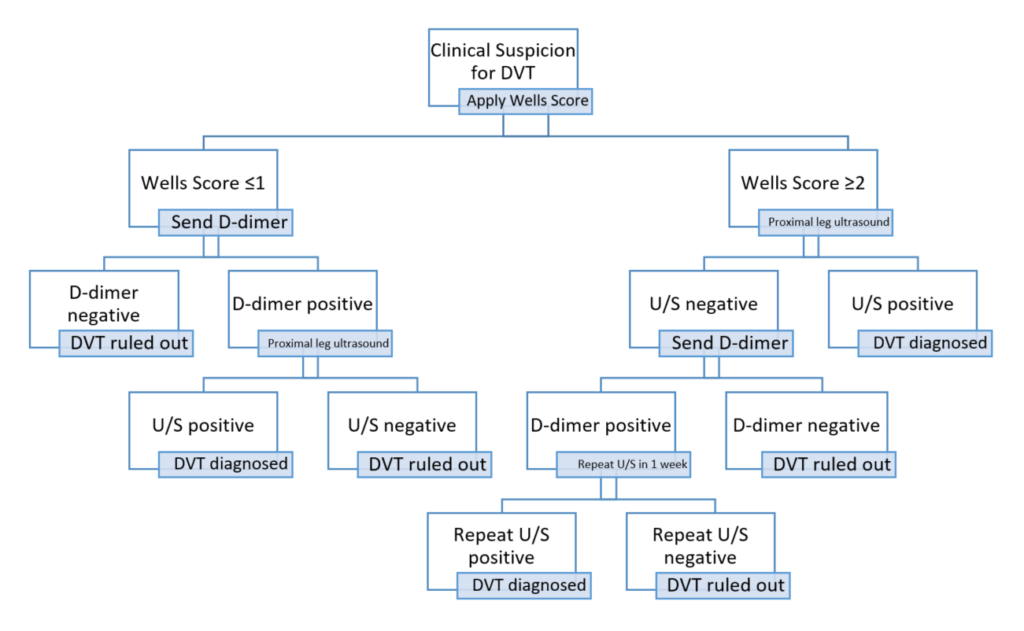

Figure 1 demonstrates that in low-risk cases work-up would begin with D-Dimer testing. In high-risk cases, as in this case, the suggested workup involves a compression ultrasound (CUS) of the proximal deep venous system, with a D-dimer added if the CUS is negative. If the CUS shows thrombus, proximal DVT is diagnosed and anticoagulation started. However, if the initial CUS is negative, further management depends on the d-dimer: if the d-dimer is negative, no further workup is required; if the d-dimer is positive, then a repeat CUS in 1 week is recommended. In the second case, if the follow-up CUS is positive, then a proximal DVT is diagnosed; if negative, no further investigations are needed. Note that at no point are the distal deep veins investigated at all – there is no way to diagnose isolated distal DVT following this algorithm.

Figure 1 – NICE diagnostic algorithm4,5

What if our investigations are guided by the CHEST guidelines?

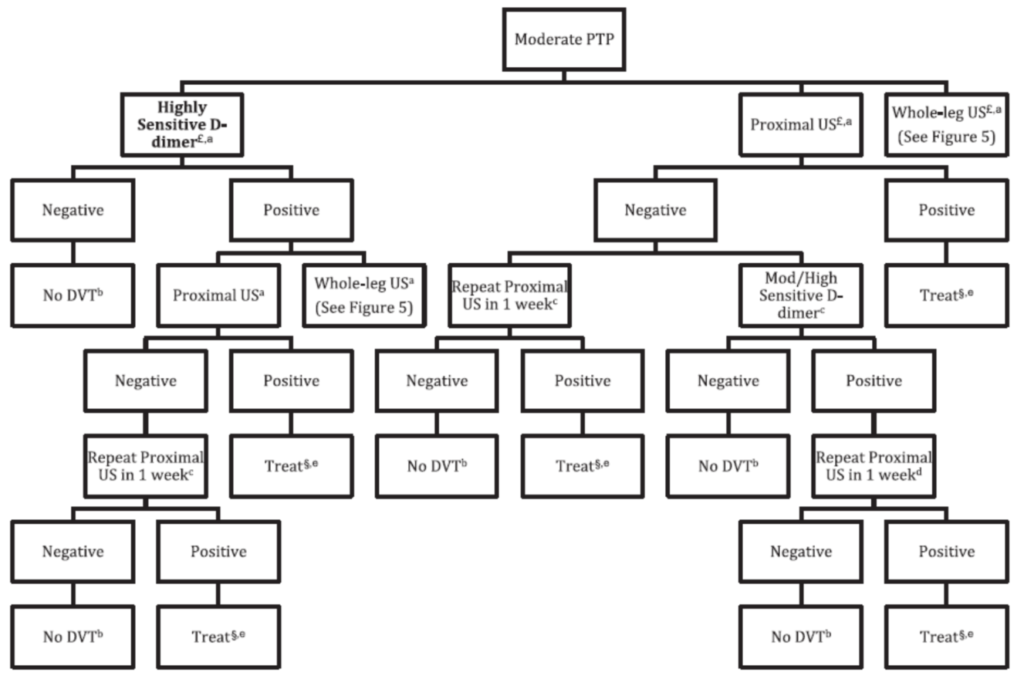

The initial step is using the Wells score to risk stratify into 3 tiers: low, medium, and high pre-test probability. For moderate probability cases, as in ours, the CHEST guidelines recommend any of the following investigations: D-dimer, proximal leg US, or whole-leg US as an initial test. The decision to use a D-dimer or US depends largely on the probability of having a false positive D-dimer. In our patient, an older woman with recent surgery, we have good reason to suspect the D-dimer would be positive with or without a DVT; therefore an ultrasound would be the better investigation. The decision to use a proximal US or a whole-leg US depends largely on how feasible it is to have a patient return for a second ultrasound. Like the NICE guidelines, the CHEST guideline recommends a repeat proximal US in 1 week if the initial one is negative and there is either a moderate-high pretest probability or a positive D-dimer. A negative whole-leg ultrasound, however, requires no follow-up imaging,2 so may be preferred if arranging a follow-up scan is difficult.

Figure 2 – Diagnostic Algorithm for moderate pre-test probability, 2012 CHEST guidelines 2 (Figure 5 in the guideline)

So, to recap: the NICE guidelines do not suggest looking for an IDDVT. They also do not discuss treatment of IDDVT presumably because they don’t suggest ever testing for it. In contrast, the CHEST guidelines suggest that we should consider whole-leg ultrasounds in patients for whom repeat US testing may be difficult. If we are ordering tests that can diagnose IDDVT, as per CHEST 2012/2016, then perhaps we should be treating them as well.

Why the discrepancy between the two guidelines?

Largely, this is because there is no certainty about how much clinical importance to attach to IDDVT. Good data on the natural history of IDDVT, their risk of extending to become proximal DVT, their risk of embolization to cause PE, their risk of recurrence, and their risk of causing post-thrombotic syndrome are still lacking. While PE in the setting of IDDVT has been well documented, it is not clear if these IDDVT had extended into the proximal veins at the time of embolism and the clinical significance of these PEs is unclear.7

Some observational data suggests that IDDVTs are at higher risk for extension and recurrence than proximal DVTs,8 but estimates for rates of extension range from 0-20%.9,10 Some RCT evidence does suggest extension of IDDVT clot burden can be prevented with anticoagulation. 10However, the absolute size of this risk reduction depends on the rate of propagation in the absence of anticoagulation, which is uncertain.

An RCT comparing proximal leg US with d-dimer to whole-leg US diagnostic strategies showed that whole-leg US diagnosed IDDVTs but did not affect rates of symptomatic VTE recurrence. 11The CHEST guidelines here suggest two possible options. In light of the fact that IDDVTs only typically cause serious sequelae if they propagate, and most IDDVTs propagate within the first 2 weeks if they do at al,8 there are two recommended treatment options. The first is to repeat whole-leg ultrasound exams at 1 and 2 weeks to look for extension of clot, either within the calf veins or into the proximal veins. If any extension is seen, CHEST suggests anticoagulant therapy to decrease the risk of further extension, PE, and recurrence. If no extension is seen after 2 weeks, then no therapy or further testing is necessary. The second approach is to begin anticoagulation at the time of diagnosis. The suggested duration of therapy is the same whether started after extension or at the time of diagnosis: 3 months.

It’s not a black and white choice between the two options. The risk of clot extension plays a large role: unprovoked clots, large clots (>5cm length, >7mm diameter, >1 vein involved), active cancer, a very high D-dimer, history of previous VTE, and inpatient status are all suggested as factors increasing the risk of extension and making initial anticoagulation a more attractive option. Conversely, a high risk of bleeding would make initial observation more attractive. The only randomized controlled trial on anticoagulation for IDDVT, the CACTUS trial, compared low-molecular weight heparin to placebo in patients with IDDVT without cancer or previous VTE. There were no differences found in rates of proximal extension or pulmonary embolism, but the study was underpowered.12 There’s lots of room for patient preference here given the lack of high-quality evidence.3 Patients may have strong feelings about the risk of taking an anticoagulant, which may not be necessary, and about the inconvenience of returning for serial exams.

[bg_faq_end]Case Conclusion:

[bg_faq_start]Given her moderate pre-test probability and strong desire to avoid repeat imaging, you decide to investigate with a whole-leg ultrasound. US shows a 4.5 cm x 5 mm clot in the tibial vein. In considering the risk of bleeding on anticoagulation and her lack of risk factors for clot extension, you discuss the options of repeat US versus anticoagulation with the patient. Despite her travel plans, she balks at the idea of taking a blood thinner for 3 months that she may not need and opts for serial whole-leg ultrasounds. There is no clot extension seen at 1 or 2 weeks, and she recovers uneventfully on the Florida beach.

[bg_faq_end]References

Reviewing with the staff (Dr. V. Bhagirath)

The issue of isolated distal DVT (IDDVT) is a thorny one. For the clinician needing to diagnose or rule out DVT, the biggest deciding factor on how to proceed may be the test that is offered by the local ultrasonography department. If whole-leg ultrasound is not available, then the question is moot. In such a case, it is reassuring to know from RCT evidence (Bernardi et al JAMA 2008) that a strategy of proximal ultrasound with repeat ultrasound in the case of positive d-dimer will not result in any significant number patients developing recurrent VTE, at least in the case of standard-risk patients. It is important, though, to properly counsel patients to return for assessment in case symptoms of extension or embolization develop. If whole-leg ultrasound is available, there exists the possibility of exposing patients to the inconveniences and bleeding risks associated with anticoagulants when their IDDVT would have fared just as well without any treatment at all. On the other hand, you may be able to spare patients the inconvenience of returning for a second visit. In the case of a whole-leg ultrasound strategy, it is important that the ultrasonographer is well-trained and experienced, as the sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound for distal DVT varies depending on the operator. (Goodacre S et al. BMC Med. Imaging, 2005;5:6; Elias A et al. Thromb. Haemost., 2003; 89:221) Once IDDVT is diagnosed, there are few data to guide treatment. The CACTUS trial randomized patients with IDDVT who did not have active cancer or previous VTE to low molecular weight heparin or placebo, in a double-blind fashion.(Righini et al. Lancet Haematology. 2016; S2352-3026:30131.) No statistically significant difference was seen in extension to proximal veins or development of PE, although the study was underpowered and confidence intervals relatively wide. Previous, lower-quality studies provide conflicting results. In my institution (Hamilton Health Sciences), we do not perform whole leg ultrasound due to concerns about its accuracy as well as the relative lack of evidence supporting anticoagulant treatment of IDDVT. At institutions where whole-leg ultrasound is performed, patients with IDDVT may be stratified by risk of bleeding and progression of VTE. Those who are at acceptable risk of bleeding who have higher risk of progression due to malignancy, inpatient status, previous VTE, or severe symptoms may be treated, while others may be offered serial ultrasound.