A 58 year old right hand dominant painter presents to the emergency department with right shoulder pain. The pain started after he returned a particularly forceful serve during a tennis match earlier that afternoon. He states that it has a similar quality to the shoulder pain he typically feels at night, but more intense and not improving with analgesia. He did not feel a “pop” or other mechanical symptoms, but has dislocated that shoulder in the past. His shoulder is swollen and tender to touch.

Background

The shoulder permits a huge range of motion but at the expense of instability and potential for injury. The shoulder is a ball and socket joint formed from three bones – the clavicle anteriorly, the humerus, and the scapula posteriorly (with its glenoid, coracoid, and acromion processes) and four joints – glenohumeral, acronium-clavicular, sternoclavicular, and scapulothoracic. The labrum is a ring of strong, fibrous tissue that surrounds and deepens the glenoid fossa.

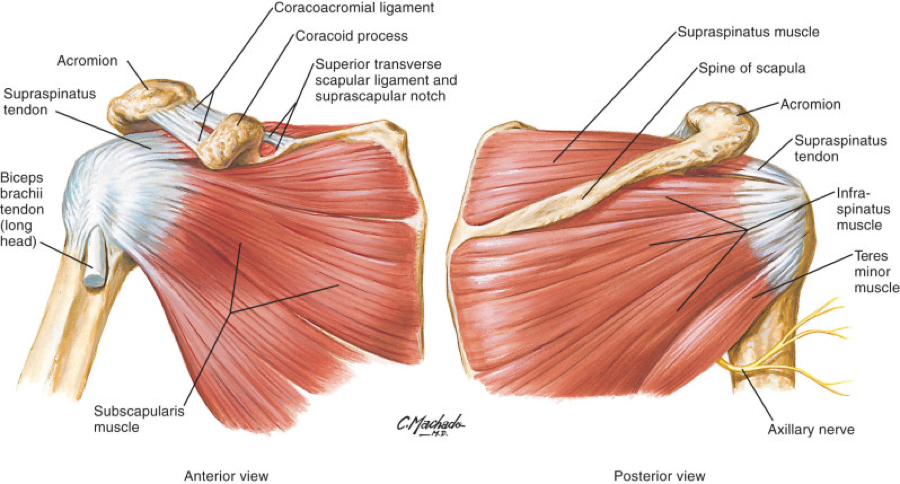

Muscles of the Rotator Cuff1

The rotator cuff consists of four muscles that stabilize the glenohumeral joint. They all attach the scapula to the humerus. The supraspinatus muscle is most superior and works with the long head of the biceps and subacromial bursa to facilitate overhead movement of the shoulder. Impingement syndrome occurs when pathologic changes to these structures, often due to chronic overuse, results in thickening and fibrosis in this space thereby preventing smooth motion. Inferior and posterior to the supraspinatus muscle is the infraspinatus muscle, followed by the teres minor, and then subscapularis muscle in a counter clockwise direction.

| Muscle | Action | Innervation |

| Supraspinatus | Abduction | Suprascapular |

| Infraspinatus | External rotation | Suprascapular |

| Teres Minor | External rotation | Axillary |

| Subscapularis | Internal rotation and Adduction | Subscapular |

Functions of the Muscles of the Rotator Cuff

Approach to the History

A thorough history can provide several diagnostic clues and help risk stratify patients. In some cases patients are in too much pain to conduct a reliable physical examination, so the history helps to form an overall impression.

- History of Presenting Illness: The timing and natural history of the injury is essential in differentiating between an acute or chronic injury, each with different investigative and management considerations.

- Pain characteristics: Identify the onset, location, quality, radiation, severity, and duration of the pain. Pain with certain patterns of provocative movements can help localize pathology.

- Associated symptoms: The presence of stiffness, reduced range of motion, parasthesias, and instability suggests muscloskeletal or nerve injury i.e. cervical radiculopathy.

- Review of symptoms: Associated symptoms including neck pain, abdominal pain, or chest pain may suggest secondary etiologies of shoulder pain referred from the chest or diaphragm. Ask about other joint symptoms to exclude a polyarticular arthritis.

- Social history: Chronic shoulder injuries are often due to overuse from employment or recreational sports activities. Ask about the patient’s level involvement in sports and exercise as they may require guidance on ‘return to play.’

Approach to the Physical Examination – ‘Look, Feel, Move’

Begin with an assessment of the patient’s vitals and overall appearance to exclude intrathoracic trauma that requires urgent intervention (ex. a tension pneumothorax) or disorders of the cardiovascular or biliary tree that may cause referred pain to the shoulder. Vague shoulder pain with a normal physical examination should increase suspicion of an extrinsic etiology. As always, examine and compare the asymptomatic and symptomatic shoulders.

- Inspection: Examine the shoulder joint for any swelling, erythema, or surgical scars. Check your patient’s resting posture for any asymmetry. Step deformities of the clavicle or acromioclavicular joint indicates fracture or separation. Winging of the scapula, best appreciated when the patient pushes up against a wall, indicates damage to the serratus anterior muscle and injury to the long thoracic nerve.

- Palpation: Beginning at the sternum palpate the sternoclavicular joint assessing for stability, warmth, and tenderness. Systemically move across the clavicle to the acromioclavicular joint, then palpate around the head of the humerus in the glenohumeral joint, and finally along the spine of the scapula. Assess the muscles of the rotator cuff, biceps, and triceps for atrophy and tenderness especially at points of insertion.

- Range of Motion (ROM): Allow the patient to perform active ROM first, followed by passive ROM feeling for crepitus. Normal ROM spans abduction to 180°, adduction (arms crossed in front of the body) to 45°, flexion to 180°, extension to 45°, external rotation (arms at the side and elbows flexed to 90°, ask the patient to rotate their arms externally) to 45° or overhead reach to T4, internal rotation to 45° degrees or underarm reach to T8-T4. Deficiencies in certain planes of motion helps to localize injury to a specific rotator cuff muscle.

- Power: Test power in flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction, comparing both sides.

- Special Tests:

Videos of the special tests from Physiotutors are linked below:

Rotator Cuff Tear:

- Painful arc and drop test: Pain with abduction past 90° and an inability to smoothly lower the affected arm could suggests a supraspinatus tear, subacromial impingement, or subacromial bursitis

- Lift off test: Instruct the patient to internally rotate their shoulder such that the back of their hand rests on their low back. Ask the patient to lift-off from their back against resistance. Pain suggests a subscapularis tear.

- Hornblower’s sign: Place the seated patient in 90° of abduction and 90° elbow flexion. A positive test is failure to externally rotate against resistance, and indicates a tear to teres minor.

Impingement:

- Neer’s: Assist the patient in passively flexing their outstretched arm overhead. Pain when their arm is “Neer” the ear is a positive test.

- Hawkins Kennedy: Flex the patient’s shoulder and elbow to 90°, internally rotating the head of the humerus against the rotator cuff. Pain with provocation suggests impingement.

- Jobe/Empty Can: With both arms in forward flexion (abduction to 45° and flexion to 45°) ask the patient to twist their arm in internal rotation as if they are emptying a can onto the ground. A positive test is pain with resistance against abduction. This test also isolates a supraspinatus tendon tear.

| Test | Sensitivity | Specificity | Likelihood Ratio (LR) |

| External Rotation Lag | 47% | 94% | 7.2 |

| Internal Rotation Lag | 97% | 83% | 5.6 |

| Resistance to External Rotation | 63% | 75% | 2.6 |

| Painful Arc | 71% | 81% | 3.7 |

| Drop Arm | 24% | 93% | 3.3 |

| Lift Off | 34-68% | 50-77% | 1.4-1.5 |

| Neer’s | 64-68% | 30-61% | 0.98-1.6 |

| Hawkins Kennedy | 76% | 48% | 1.5 |

| Jobe | 71% | 49% | 1.3 |

Clinical Utility of Special Tests in the Shoulder Exam2

Stability:

- Sulcus sign: Grasp the head of the humerus and pull downwards, checking for a sulcus at the anterior humerus indicating inferior instability.

- Load and Shift test: Grasp the head of the humerus and attempt to translate it forward and backwards, checking for anterior and posterior instability.

- Apprehension test: With the patient lying supine, gently abduct and externally rotate the shoulder with one hand, and apply upwards pressure anteriorly with the other hand. A positive result is pain or fear with this guided movement, but the test is always done in combination with the Anterior Relocation test.

- Anterior Relocation test: Continuing from the apprehension test, now apply a downward pressure on the humerus. If this relieves the patient’s pain it again suggests anterior dislocation.

- Anterior Release test: Continuing from the relocation test, a positive test occurs if the patient expresses pain when the examiner’s hand is suddenly removed.

The Anterior Release Test has the highest LR for instability at 8.3 with a sensitivity of 92% and a specificity of 89%, followed by the relocation test with a LR of 6.5, sensitivity of 85% and specificity of 87%3.

Bicep Tendonitis:

- Speed’s: Apply downward pressure to the patient’s straight arms in forward flexion (imagine that they’ve just bowled). Pain against resistance in the bicepital groove is positive for bicep pathology.

- Yergason’s: Hold the patient’s wrist as if giving them a handshake, have them attempt to pronate and supinate against resistance and assess for pain.

- O’Brien’s sign: Position the patient in 90° of shoulder flexion and 10° of adduction with their elbow fully extended and thumbs pointing down, then push down on their arms. Pain and mechanical symptoms with resistance that then resolves with supination is a positive test. A positive test indicates a SLAP tear (superior labral tear from anterior to posterior), which is often comorbid with bicep tendinopathy.

- Neurovascular exam: The neurovascular exam must be conducted before and after every reduction. Sensory function should be tested with both light touch and pinpoint.

| Nerve | Origin | Motor function | Sensory function | Reflexes |

| Axillary | C5,6 | Deltoid: arm abduction | Deltoid muscle | |

| Musculocutaneous | C5,6 | Biceps: elbow flexion | Lateral forearm | Biceps |

| Radial | C6,7,8 | Triceps: elbow extension | Anatomic snuff box | Triceps brachioradialis |

| C7,8 | Wrist extensors: wrist extension (thumbs up sign) | ½ of the dorsal side of the radius towards the thumb | ||

| Medial | C6,7 | Flexor pollicus longus: Thumb flexion (OK sign) | Palmar side of 3 ½ fingers | |

| Ulnar | C8, T1 | Interossei: Finger abduction and adduction | 5th finger | |

| Suprascapular | C5-C6 | Supraspinatus and Infraspinatus | Subscapularis |

Neurologic examination4

Vascular injury may manifest as asymmetric weak distal pulses, parasthesias, or an expanding hematoma. The risk of vascular injury is higher in displaced fractures and in elderly patients with atherosclerosis.

Nerve injury can present with weakness, parasthesias, and muscular atrophy. Thoracic outlet syndrome occurs with compression of the trunk of the brachial plexus and subclavian vessels in the tissue between the neck and axilla.

- Neck exam: Degenerative cervical spine injuries may compress nerve roots and cause referred pain to the shoulder.

Investigations

X-rays of the shoulder should be ordered as three views:

- AP or 45 degree lateral (avoids bony overlap on the shoulder joint). These views will show a dislocation.

- Transcapular ‘Y view’ to show the direction of the dislocation (anterior or posterior).

- Axillary, although this is often difficult to obtain due to patient pain and restricted ROM.

In the context of a shoulder dislocation X-rays should be obtained before reduction attempts unless there are signs of neurovascular injury or skin tenting. Shoulder dislocations and proximal humeral fractures with subluxation may appear similarly on clinical exam but have drastically different management, the later often requiring orthopedic consultation and potential operative intervention5. Some physicians will forgo an X-ray prior to reduction in a patient with a history of recurrent dislocations with a history and physical exam consistent with dislocation in the absence of significant trauma. Generally, more advanced imaging including CT, MRI, and US are arranged in the outpatient setting after discharge from the Emergency Department, the exception being ultrasound for a clinical significant tendon injury i.e. biceps tendon. CT imaging may provide more detailed views of bony structures while MRI shows soft tissue injuries and tears. Ultrasound may be used to identify rotator cuff, labral, and biceps tendon tear but is highly operator dependent6.

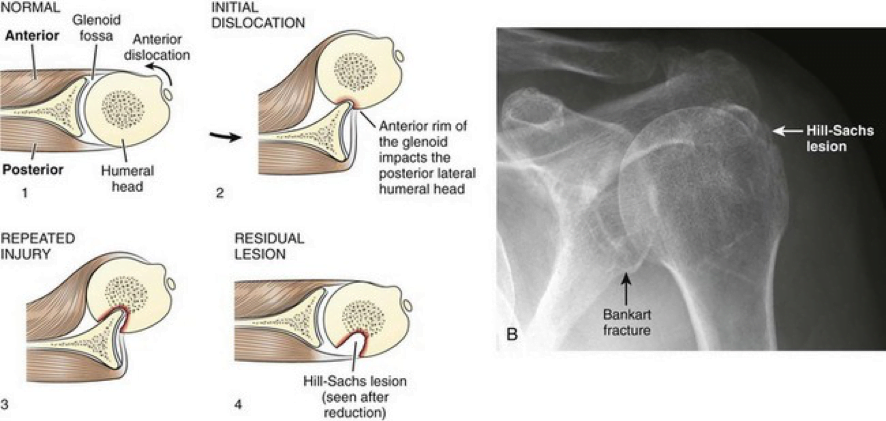

Traumatic injuries to the shoulder may result in Hill-Sachs lesions. These are compression fractures of the posterior humeral head resulting from contact with the glenoid rim, typically in the setting of an anterior dislocation. A Hill-Sachs lesion may be accompanied by a Bankart lesion: an avulsion of the anteriorinferior glenoid labrum from the glenoid rim.

Mechanism and Appearance of Hill-Sachs and Bankart Lesions7

Putting it all together

The combination of the history, physical, and ancillary test results can help to guide your assessment:

| Injury | Mechanism | Signs and Symptoms | Investigations |

| Posterior Glenohumeral Dislocation | Rare, as the scapula and thick posterior musculature generally prevents dislocations. Etiologies are often traumatic and associated with the “3 Es:” ethanol, epilepsy, and electricity and dislocations may be bilateral. | Internally rotated arm in adduction, pain with external rotation and abduction. Flattening of the affected shoulder. Prominent coracoid. Positive posterior apprehension test. | X-rays show the humeral head posterior to the glenoid fossa; best seen on axillary views. AP views may show the “light bulb sign” where the internal rotational of the humeral head causes it to lose its asymmetrical appearance8. |

| Anterior Glenohumeral Dislocation | Direct force generally to an abducted externally rotated arm (ex. athletic injuries). May be recurrent. | Externally rotated in abduction, pain with internal rotation. Squaring off of the affected shoulder. Positive apprehension, relocation, and release test. | X-ray shows the humeral head anteriorly. A Hill-Sachs deformity or Bankart lesion is pathognomonic. Neurovascular exam may show injury to the axillary nerve. |

| Acromio-clavicular Joint Separation/ Dislocation | Traumatic fall or blow. | Noticeable step deformity, best viewed when the patient is sitting upright. Pain with palpation. Limited ROM especially with adduction and when crossing the affected arm across the body. | X-ray (esp. the Zanca view) is used to grade the separation using the Rockwood classification; this determines whether operative management is indicated. |

| Clavicle Fracture | Traumatic fall or blow. | Pain with palpation. Noticeable step deformity with possible skin tenting. May be associated with a sternocleidomastoid muscle spasm, where the patient’s head is flexed towards the fracture and rotated away. | Neurovascular exam is necessary to rule our brachial plexus and subclavian vessel injury. Management depends on location of the fracture and the Allman classification of the fracture. Middle third fractures are most common and managed conservatively. |

| Humeral Fracture | Trauma including direct blow, fall on an outstretched abducted arm. | Pain, swelling, tenderness, limited ROM with arm typically held in adduction close to the body. | Neurovascular exam may show injury to the axillary and suprascapular nerve. Fractures are visible on X-ray. |

| Impingement Syndrome (subacromial bursitis, supraspinatus tendinitis, painful arc) | Chronic, repetitive, overhead movement. | Insidious onset pain, often at night, worsening with overhead movement. Crepitus, weakness secondary to pain. Pain with provocative special tests. | X-rays are non specific but may show degenerative changes including sclerosis, and cyst or spur formation. |

| Rotator Cuff Tear | Acute traumatic injury (ex. trauma, glenohumeral dislocation) or acute on chronic pain especially in older adults. | Swelling if acute, muscle atrophy if chronic. Painful arc, weakness, and reduced active ROM. Discrepancy between active and passive ROM suggests a tear. | Diagnosis is clinical, although X-rays may show narrowing of the acromiohumeral space. Ultrasound may be useful in screening for tears9. |

| Calcific Tendinitis | Rotator cuff pain, potentially bilateral, often at night and more common in females. | Limited ROM with a painful arc and pain on palpation. | X-rays may show calcium deposits. |

| Adhesive Capsulitis “Frozen Shoulder” | Primary/idiopathic (associated with diabetes, thyroid disorders, and autoimmune diseases) or secondary from shoulder injury. | Restrictive shoulder movement from capsular thickening and scarring progressing from a freezing to frozen to thawing phase. Muscular atrophy. Pain is often most severe at night and localized to the deltoid. | Clinical diagnosis. Neurovascular exam is necessary to rule out nerve injury. |

| Bicep Tendinopathy | Acute or chronic tenditis (inflammation) or tendinosis (tears). May be associated with labrum tears. | Pain with palpation in the anterior shoulder and along the biceps groove. Pain with forearm supination; a positive Speed’s or Yergason’s test. A “Popeye” muscle indicates a complete bicep tear. | Clinical diagnosis. Imaging may show a reduction in the subacromial space. |

| Superior labrum anterior to posterior (SLAP) tear | Repetitive overhead movements, especially in labourers and athletes who throw overhead | Range of motion is often accompanied by mechanical symptoms such as clicking or catching. Positive O’Brien’s. | Clinical diagnosis. Imaging may be used to rule out other pathology. |

Management

Successful reduction of an anterior shoulder dislocation is indicated by an improvement in anatomy, pain, and range of motion. There are several methods to reduce anterior shoulder dislocations, all of which (and more!) can be seen in video tutorials:

- Stimson: have the patient lay prone with their dislocated arm hanging over the edge of the stretcher with a 5-15lb weight attached (or use 4 1L bags of saline in a stocking). Reduction typically occurs within 15-20 mins.

- Scapular Manipulation: Position the patient as in Stimson, but use both hands to push the tip of the scapular medially, repositioning the glenoid fossa over the humeral head.

- External Rotation: Position the patient supine with their elbow flexed to 90°. With one hand on the patient’s wrist and the other on their elbow ask the patient to slowly externally rotate their arm. Reduction occurs as the arm is externally rotated.

- Milch: Position the patient supine with their elbow flexed to 90° and their arm externally rotated. Slowly abduct the arm through 180° of motion, stopping if there is resistance until the patient is relaxed. In-line traction towards the humeral head may be applied if the first attempts are unsuccessful. The FARES method adds vertical oscillation throughout this movement.

- Traction/counter traction: Abduct the patient’s arm and flex the elbow to 90°. Apply traction on the arm while an assistant provides counter traction to the torso by pulling on a sheet wrapped around the patient’s chest.

- Cunningham: Sit across from the upright patient and place the elbow of their dislocation arm on your shoulder. Massage and relax their deltoid and bicep muscle while they shrug their shoulders.

A recent systematic review found that scapular manipulation is the quickest and most successful technique. The FARES technique also has high success rates with a short reduction time, with the added benefit of reduced pain and less need for intravenous analgesia. The traction-counter traction method has high success rates, but typically takes longer and often requires procedural sedation10. Posterior shoulder dislocations are reduced through a traction/counter traction technique. Pain during reductions can be managed with procedural sedation, or intra articular lidocaine or bupivacaine injections11.

Ultrasound can also be used to detect dislocation, with a reported sensitivity and specificity of 100%12. However results are highly operator dependent and scanning protocols are not well defined, therefore its clinical use might be more suited for confirming appropriate reduction at the bedside potentially avoiding the need for re-sedation in the case of persistent dislocation. Post-reduction care should still include a neurovascular exam and confirmatory X-rays.

The Neer system classifies humeral head fractures based on the location of fracture segments and the amount of displacement and angulation, not on the number of fracture lines. One part fractures involve <1cm or <45° of displacement and can be managed conservatively with sling, ice, early mobilization and outpatient orthopedics follow-up. More severe fractures require an orthopedics consult. Extensive and angulated fractures of the humeral head are at risk of ischemic necrosis. A significantly displaced fracture may also involve rotator cuff tears, and these are best reduced in consultation with orthopedics as manipulation can worsen the alignment of previously non-displaced segments.

Reduced dislocations should be supported in a shoulder immobilizer. The patient should be advised to adopt early ROM exercise of the elbow to avoid stiffness and should have orthopedic follow-up within about a week. Impingement syndromes and calcific tendinosis should be managed conservatively with anti-inflammatory analgesia, ice, and gentle range of motion exercises (ex. pendulum swings, finger wall walks) and physiotherapy. The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons has published a shoulder strength and conditioning program with printable handouts13.

Back to the Case

The history makes you suspicious of a chronic impingement syndrome. Physical examination shows pain and unilateral weakness with abduction, although passive ROM is well preserved. There is a positive painful arc, Neer’s and Jobe’s test. The shoulder joint feels well positioned and is stable throughout testing, but you order X-rays to assess alignment given the possibility of dislocation recurrence. X-rays show generalized sclerosis but are otherwise normal. You suspect that this patient has a supraspinatus tear. You give instructions on conservative management, and refer to the patient’s family physician on an outpatient basis for further assessment.

Good Resources

- Rheumtutor: MSK Clinical Skills Manuals and Instructional Videos

- Orthobullets: Quick reference orthopedic information

- Physiotutor: Youtube videos for clinical assessment

- American Society for Sports Medicine: Video demonstrations of shoulder ultrasound. Users must make a free account to access the videos

- NEJM: Video demonstrating a comprehensive clinical examination of the shoulder

References

Reviewing with the Staff

This is a review of ‘shoulder pain’ as an emergency department presentation. It focuses primarily on musculoskeletal anatomy and physiology and both traumatic and non-traumatic musculoskeletal causes of shoulder pain and injuries. Although not the focus of our review, it’s important to keep a broad differential for patients presenting with ‘shoulder pain’ and consider causes originating outside of the glenohumeral joint, for example medical causes i.e. pain from acute coronary syndrome, diaphragmatic irritation from a ruptured ectopic pregnancy, as well as musculoskeletal causes i.e. a cervical radiculopathy or rotator cuff disease. We’ve also included an evidence based approach to the shoulder examination and an in-depth look at the role of x-rays in the diagnosis of shoulder injuries. I highly recommend the video links provided for the shoulder examination and reduction methods for glenohumeral dislocations.