This updated episode of CRACKCast covers Rosen’s Chapter 33 (9th Ed.) on multi-traumas. This episode will outline the approach and details of the diagnosis and treatment for patients with multiple, often high stakes, injuries.

Shownotes – PDF Here

[bg_faq_start]Rosen’s in Perspective:

Alright, guys, we are back at it again. Let’s start things off with a case.

You are working your local level one trauma centre when you get a page from your ED triage nurse. You pick up the phone and you get the following story:

45Y female in high-speed rollover MVC with suspected injuries to the C-spine, face, pelvis. Obvious open ?femur fracture to the left leg. Hypotensive and tachycardic at-scene. Passenger in car pronounced dead on scene.

Every word seems to strike more anxiety into your soul. What do you do? How do you prepare the room and your team?

If this case scares you as much as it does us, have no fear. We got you, as always. Today’s episode will be the introductory podcast for the upcoming section on trauma. While it may seem rather general, we have tried to pack all of the pearls we could into it to prime your minds for the podcasts to come. In today’s episode, we will give you all the tools you will need to skillfully wade into the waters of the trauma world. We will review a solid approach to the trauma patient, detailing the components of the primary and secondary surveys. We will break down the use of POCUS in trauma scenarios as well as give you the information you will need to select appropriate ancillary and diagnostic imaging tests during your next visit to the trauma room. Last, we will end things with the Rosen’s trivia you have all come to know and love.

With that, we will giddy up along the trail. So, grab a coffee, sit back, and enjoy the ride!

[bg_faq_end]Core Questions:

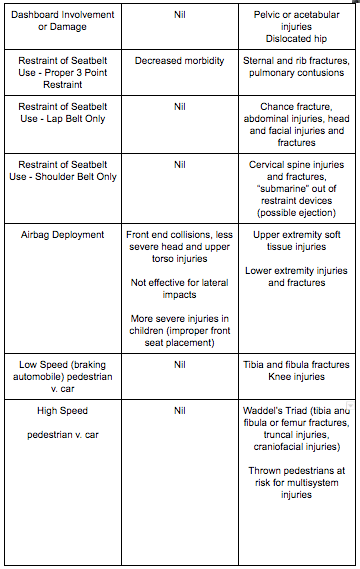

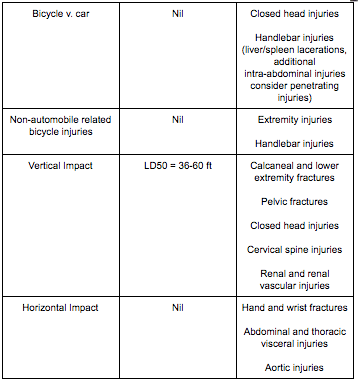

[bg_faq_start][1] What are the injuries for the following blunt trauma mechanisms:

This table was adapted from Table 33.1 – Blunt Trauma and Associated Injuries in Rosen’s 9th Edition. Please refer to the text for further details.

[2] Outline an approach to the primary survey for the trauma patient.

[3] Describe the elements of the eFAST exam.

Alright. This is a foundational skill that ALL practitioners of Emergency Medicine must be well-versed in. While this brief explanation most certainly will not give you competence in ultrasound, hopefully it will pique your interest enough to learn more.

Components of the eFAST Exam

- Check for lung slide bilaterally – assesses for pneumothorax

- Check for pericardial effusion with a subxiphoid view of the heart – assesses for potential cardiac tamponade in context of blunt trauma

- Check for free fluid in:

- RUQ – this view also helps to identify hemothorax

- LUQ – this view also helps to identify hemothorax

- Pelvis

Notes on Testing Results:

- For free fluid in the abdomen

- 42% sensitive, >/98% specific

- As little as 100 cc of free fluid can be detected

[4] Outline an approach to the secondary survey in the trauma patient.

This table was adapted from Table 33.2 – Secondary Survey of Trauma Patients in Rosen’s 9th Edition. Please refer to the text for further details.

[5] Detail relevant ancillary laboratory tests to order in the trauma patient.

While this is by no means an exhaustive list, consider ordering the following studies in the patient who has experienced blunt trauma:

- CBC

- Electrolytes

- Extended electrolytes

- Liver enzyme and function testing

- INR/aPTT

- Urinalysis + Creatinine/BUN

- Blood type and screen or crossmatch (depending on severity of injury and suspicion of impending transfusion)

- VBG with lactate

- Trops/CK

- B-HCG

[6] List the components of the following imaging decision-making tools: Canadian CT Head Rule, Canadian C-Spine Rule, NEXUS C-Spine Rule, NEXUS Chest Rule

Canadian CT Head Rule:

-Medium risk (for brain injury on CT)

- Amnesia before impact >30 min

- Dangerous mechanism (pedestrian struck by vehicle, occupant ejected from motor vehicle, fall from elevation >3 feet or 5 stairs or more

-High Risk (for neurological intervention)

- GCS <15 at 2 hours post injury

- Suspected open or depressed skull fracture

- Signs of basilar skull fracture (hemotympanum, racoon eyes, CSF otorrhea/rhinorrhea, Battle’s sign)

- Age >65 years

- Two or more episodes of emesis

In addition to the risk factors, it is important to remember the inclusion and exclusion criteria so that the rule can be applied in the correct patients.

Inclusion criteria:

- Minor head injury (blunt trauma to the head resulting in witnessed LOC, definite amnesia, or witness disorientation

- Initia ED GCS greater than or equal to 13

- Injury within the past 24 hours

Exclusion criteria:

- Age < 16 years

- Minimal head injury (no LOC, amnesia, or disorientation)

- Unclear history of trauma as the primary event ex. primary seizure or syncope

- Obvious penetrating skull injury or depressed skull fracture

- Acute focal neurological deficit

- Unstable vital signs associated with major trauma

- Seizure prior to ED assessment

- Bleeding disorder or anticoagulation use

- Return for reassessment for the same head injury

- Pregnancy

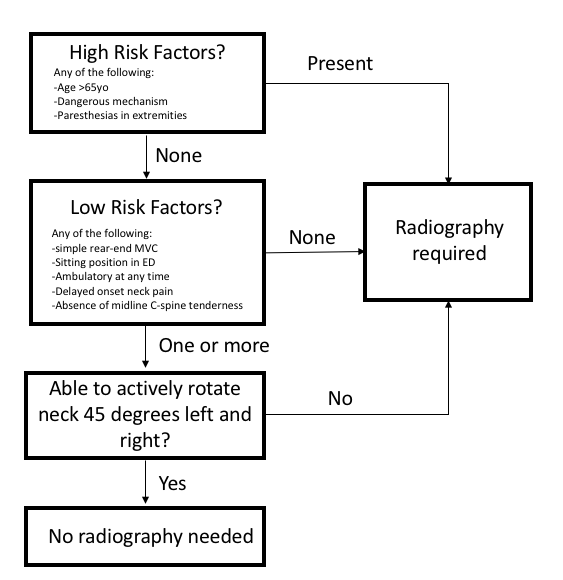

Canadian C-Spine Rule:

Canadian C-Spine Rule Exclusion Criteria:

- Age <16 years

- GCS<15

- Grossly abnormal vitals

- Injury >48 hours

- Penetrating trauma

- Acute paralysis

- Known vertebral disease (ankylosing spondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis, spinal stenosis, previous spinal surgery)

- Return visit for reassessment of same injury

- Pregnant

Nexus C-Spine Rule:

- No midline tenderness

- No focal neurological deficits

- Abnormal alertness

- No intoxication

- No painful distracting injury

**Inclusion criteria is blunt neck injury

Nexus CT Chest Rule:

-Clinically major thoracic injuries:

- Abnormal chest x-ray (absence of any thoracic injury including clavicle fracture or widened mediastinum)

- Distracting injury

- Chest wall, sternum, thoracic spine, or scapular tenderness

-All thoracic injuries:

- Rapid deceleration mechanism (fall from >20 feet/6.1m, or MVC at >64.5km/h with sudden deceleration

**If all the above criteria are met in a chest trauma no CT chest is required. Use only in awake, non-intubated, hemodynamically stable blunt trauma patient 15 years or older in whom CT chest is considered as part of the normal diagnostic evaluation.

[7] What are the indications for a CT abdomen/pelvis in the trauma patient?

As per Rosen’s 9th Edition, the following are indications for blunt trauma patients undergoing CT abdomen/pelvis imaging:

- Abdominal pain or tenderness

- Significant mechanism of injury

- Abnormal eFAST exam

- Gross hematuria

- Unreliable examination (e.g., altered mental status, distracting injury, head injury)

- Presence of a seatbelt sign

Wisecracks:

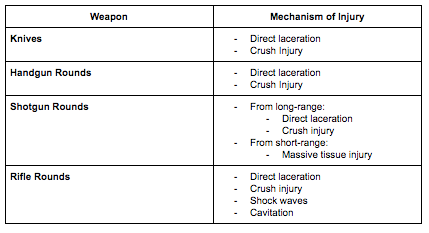

[bg_faq_start][1] What are the mechanisms of injury for the following weapons: knives, shotgun, handgun, rifle?

[2] What is the LD50 in feet for falls from a given height?

Answer: LD50 = 36-60 feet

[3] What is permissive hypotension and what evidence does it have?

Answer: THIS IS CONTROVERSIAL AND NOT WIDELY ACCEPTED

Basic Principles:

- Allow the BP to fall enough to prevent exsanguination but high enough to perfuse organs

- Want to avoid dislodgement of unstable clots that have formed

- Helps to avoid over-resuscitation that can lead to coagulopathy and death

- Only used as a damage control intervention to help the patient get to definitive intervention (e.g., surgery)

- Once you control the hemorrhage, normal physiologic parameters are met

- Meant largely for penetrating traumas

Downfalls:

- LITTLE EVIDENCE – really only based on animal studies and one semi-randomized trial in 1994

- Results in worsening secondary injury in patients with concomitant TBI’s

- While all patients who are shocky post-trauma are assumed to be experiencing hemorrhagic shock, concomitant forms of shock can co-exist. This is not an appropriate strategy for patients with other causes of their shock (e.g., obstructive shock)

[bg_faq_end]

This post was uploaded and copy edited by Ryan Fyfe-Brown