Pain is one of the most common concerns of patients presenting to the ED. Achieving excellent analgesia while minimizing side effects is an important and nuanced skill to develop. The goal of emergency pain management is not to completely eradicate pain but rather, reduce pain to an acceptable level allowing for safe discharge/return to daily activities, or to bridge until inpatient care can be arranged1,2.

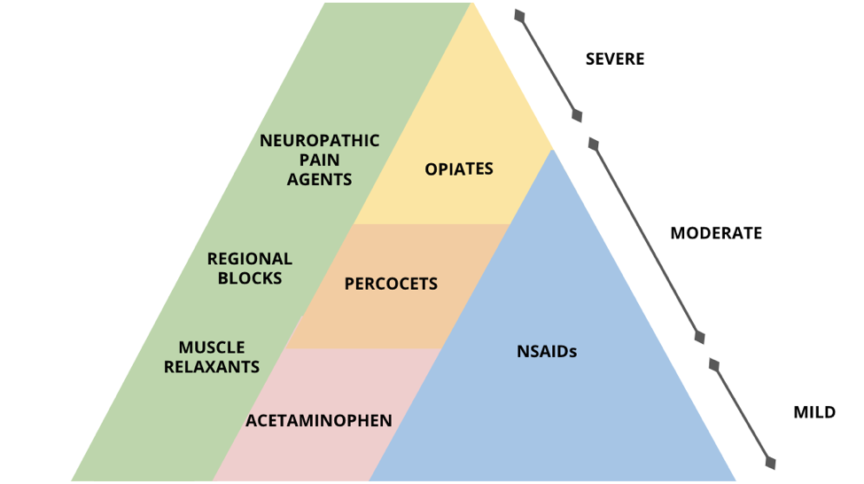

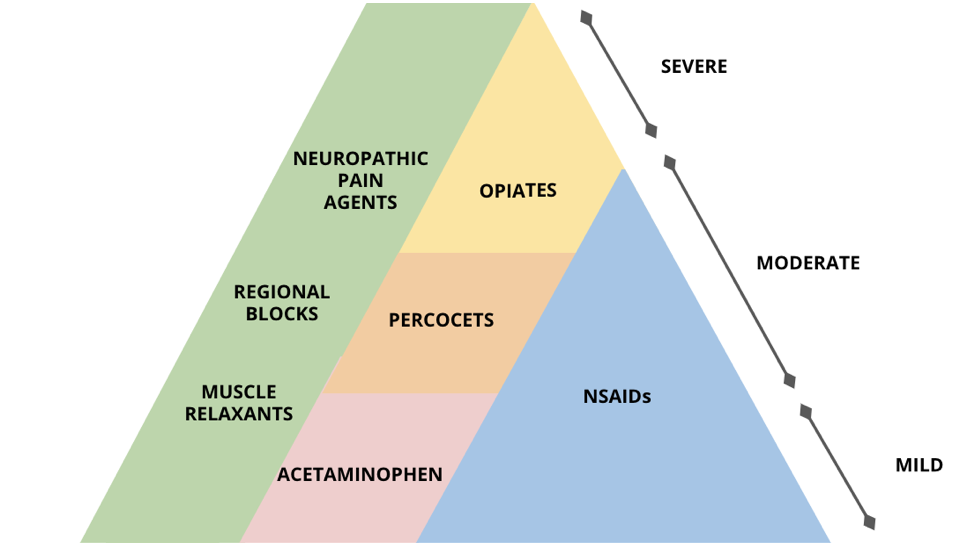

There are a number of principles of pain management to keep in mind when choosing an analgesic agent. The WHO Analgesic Ladder has been a frequently cited reference for decades and has five main themes to guide your choices3:

- Oral administration is preferred whenever possible

- Analgesics should be given regularly enough to maintain pain control

- Agents should be chosen based on reported pain intensity

- Dosing of agents should be adapted to the patient

- Patients should be given clear instructions on how/when to take their medications

The type of pain that a patient is experiencing and their medical history (e.g. medical conditions, drug allergies, current medications, etc.) will influence your analgesic choice as well but a basic understanding of what your options are and when to use them is a good starting point. This post will give you an introduction to the types of analgesics you have access to in the emergency department and when to use them.

Acetaminophen (Mild Pain)

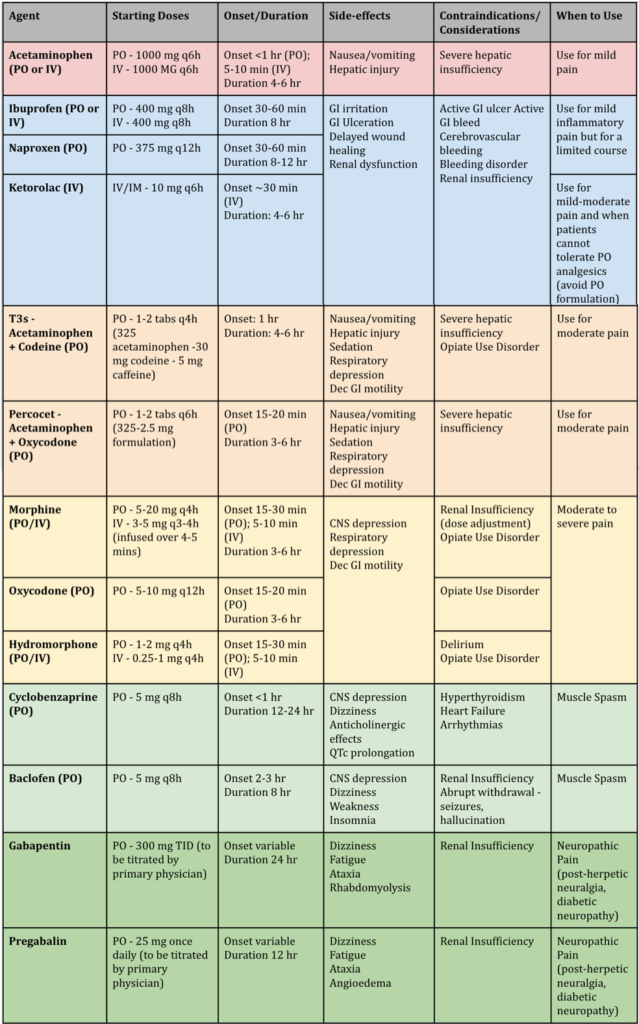

Acetaminophen (Tylenol) is often a first line agent in the ED for mild pain. This is because of the efficacy for mild pain as well as the minimal side effects that come with it. Because tylenol is metabolized by the liver, severe hepatic insufficiency is a contraindication but otherwise it is quite a universal analgesic1,2.

NSAIDs (Mild-Moderate Pain)

NSAIDs are an excellent choice for mild to moderate pain secondary to inflammation. This class of drugs is diverse and its uses can vary from MSK pain to renal colic. NSAIDs are often used as a first line agent either alone or in combination with acetaminophen. Despite their efficacy, NSAIDs have been associated with gastric bleeding, ulcers, platelet function inhibition, and nephrotoxicity. These adverse effects necessitate that these agents are used for a short course and are avoided in patients with renal disease. Common NSAIDs used in the emergency department include Ibuprofen (Advil), Naproxen (Aleve), and Ketorolac (Toradol)1,2,4. Each drug has characteristics that define the best context to use it in:

- Ibuprofen – Oral drug – best GI side effect profile

- Naproxen – Oral drug – best cardiovascular side effect profile

- Ketorolac – IV/IM drug – best for patients who cannot tolerate PO analgesia (typically used for moderate pain) ***NOTE: A PO formulation exists but should be avoided due to higher side effect profile despite similar analgesic effect4

Opiates (Moderate-Severe Pain)

Opiates are effective analgesic agents in the context of moderate to severe acute pain that cannot be adequately controlled with a non-opiate. However, this efficacy is coupled with a number of harmful side effects including: respiratory depression, sedation, tolerance, hyperalgesia, and opioid use disorder. For any outpatient script, remember that opioids are extremely constipating so always write a laxative script alongside the opioid. Great care must be taken to prescribe these drugs responsibly and under the right circumstances after appropriately educating patients about the risks and the analgesic alternatives.

The most commonly used opiates include morphine, oxycodone, and hydromorphone. Combination drugs like T3s and Percocets are often used to target moderate pain but importantly have the same addictive properties of other opiates. At equianalgesic doses, the efficacy of different opiates is the same (allowing for variance in metabolism). Oftentimes, the type of opiate used is influenced by the practitioners familiarity with dosages. Regardless when titrating opiates, “start low, go slow” is a good approach to prevent overdosing. For the elderly, it is essential to use caution as opioids can build up leading to delayed narcotic overdose1,2,5–7.

- Combination drugs:

- T3s (acetaminophen + codeine)

- Percocet (acetaminophen + oxycodone) for moderate pain

- Morphine:

- Baseline by which other opiates are measured (ME = morphine equivalents)

- Note: metabolites hard to excrete in renal failure

- Oxycodone (1.5 ME)

- Hydromorphone (5 ME)

- Neuro-excitatory metabolites hard to excrete so increased risk of delirium

The addictive nature of opiates is something to keep in the forefront of your mind when choosing what is best for your patient. Important questions to ask yourself include: Is my patient opioid naive? Is there a history of substance abuse? What is the risk of prescribing short-course PRN opioids on discharge for my patient? The Opioid Risk Tool (ORT) is a quick tool to take risk factors into consideration when making this difficult decision. In patients with elevated risk, you may choose agents with less addictive potential like NSAIDs, non-opioid analgesics or a brief opioid course with counseling. Remember that even a short term prescription carries with it real risks of creating opioid dependency. In high risk patients, consider dispensing or prescribing a naloxone kit. Advise patients to safely dispose of their opioids and to lock them up if there are dependents in the house who could inadvertently overdose through misadventure or error7.

Muscle Relaxants (Muscle Spasm)

Muscle relaxants are a class of drugs that are used to treat pain secondary to muscle spasm. Many muscle relaxants come with side effects including drowsiness and dizziness. This can keep patients from staying active and getting back to their baseline function (which are the goals of managing spasm/pain). Keeping in mind the common side effects of muscle relaxant use, it is recommended to use them in low quantities for short durations and to advise patients to avoid combining these with opioids, alcohol or benzodiazepines. Common muscle relaxants used in the emergency department include baclofen (Lioresal) and cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril)8,9.

Neuropathic Pain Medications (Nerve Pain)

Nerve pain is a common concern in the ED but it is often difficult to treat in this setting. The challenge stems from the slow onset of these medications (days to weeks) and necessity of titration to effect. The most common medications used to treat neuropathic pain are calcium channel blocker anticonvulsants including gabapentin and pregabalin. Both of these drugs have an unattractive side effect profile, despite their efficacy in cases of postherpetic neuralgia and diabetic neuropathy. Common adverse effects include dizziness, fatigue, ataxia, and rhabdomyolysis. They are excreted renally and should be avoided in those with renal insufficiency. When prescribing these, start at low doses before titrating up and advise patients to monitor for side effects. These should also be used in caution with patients already taking narcotics as they also have abuse potential10.

Other Options

[bg_faq_start]Regional Blocks

Nerve blocks are useful when pain is well localized in an area or nerve distribution (e.g. single digit, sciatica, dental). Regional blocks have the benefit of prolonged duration of pain relief but come with the cost of time needed to perform the procedure as well as risks associated with needle insertion. This is often a technique performed by more experienced or specially-trained practitioners in the department. Common agents used include lidocaine (shorter acting) and bupivacaine (longer-acting). Either agent can be combined with epinephrine to cause vasoconstriction, delaying anesthetic distribution and prolonging duration of effect. Although this is not a universally common procedure, interest has been gaining in this method of pain management in the ED11.

[bg_faq_end][bg_faq_start]Adjuncts/Non-Pharmacologic Treatments

As adjuncts to medication don’t forget that the mind plays an important role in pain. Try and ensure they have a comfortable position to sit in (where space allows). Administer ice or heat and use splints for MSK injuries. Utilize distraction (smart phones, ipads) where possible. For young children, sugar-based solutions can be used to mitigate painful procedures. Studies have shown that telling patients that their pain will be reduced can help magnify the impact of treatment11,12.

There are a number of adjunct therapies that can be used in conjunction with the above mentioned therapies. Ice and heat therapy is a common recommendation for MSK pain. Sprains and strains have been shown to respond well to topical NSAIDs like diclofenac (Voltaren). Part of your disposition plan should always involve a plan to return to activity if this is limited by a patient’s pain. Oftentimes, a multimodal approach to pain management is the most efficacious one11.

[bg_faq_end]

Takeaways

- The goal of pain-management in the ED is not zero pain, but rather reaching an acceptable level for function.

- When choosing route of delivery, oral is often preferred unless the patient cannot tolerate PO meds.

- Consider a combination of non-opiates. Starting with 1000 mg Acetaminophen and 400 mg of Ibuprofen is an ED go-to for mild-moderate pain.

- Opiates should only be used if non-opiate agents are insufficient to treat the severity of pain that the patient endorses. When using opiates, start low and go slow!

- Treat pain before ordering your workup! Do not leave your patient suffering until you get results back.

Final Thoughts

You will inevitably manage pain during every ED shift but luckily you have a diverse arsenal of agents at your disposal. As we continue to learn about how these agents compare, practice will shift and it is important to reassess why you are choosing one drug over another. When managing your patient’s pain make sure you balance efficacy with the risks associated with each agent. Always adopt a patient-centered approach and counsel extensively on the risks and side effects of each agent.

This post was edited by Megan Chu and Julia Heighton, and posted by Megan Chu.

- 1.Optimizing the Treatment of Acute Pain in the Emergency Department. Annals of Emergency Medicine. September 2017:446-448. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.06.043

- 2.Cisewski DH, Motov SM. Essential pharmacologic options for acute pain management in the emergency setting. Turkish Journal of Emergency Medicine. January 2019:1-11. doi:10.1016/j.tjem.2018.11.003

- 3.Forbes K. Pain in Patients with Cancer: The World Health Organization Analgesic Ladder and Beyond. Clinical Oncology. August 2011:379-380. doi:10.1016/j.clon.2011.04.016

- 4.Nissen SE, Yeomans ND, Solomon DH, et al. Cardiovascular Safety of Celecoxib, Naproxen, or Ibuprofen for Arthritis. N Engl J Med. December 2016:2519-2529. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1611593

- 5.National Pain Centre MGD. Canadian Guideline for Safe and Effective Use of Opioids for Chronic Non-Cancer Pain. Canadian Guideline for Safe and Effective Use of Opioids for Chronic Non-Cancer Pain. http://nationalpaincentre.mcmaster.ca/opioid/cgop_b_app_b08.html. Accessed March 26, 2020.

- 6.Banerjee M, Bhaumik D, Ghosh A. A comparative study of oral tramadol and ibuprofen in postoperative pain in operations of lower abdomen. J Indian Med Assoc. 2011;109(9):619-622, 626. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22480093.

- 7.Barnett ML, Olenski AR, Jena AB. Opioid-Prescribing Patterns of Emergency Physicians and Risk of Long-Term Use. N Engl J Med. February 2017:663-673. doi:10.1056/nejmsa1610524

- 8.Witenko C, Moorman-Li R, Motycka C, et al. Considerations for the appropriate use of skeletal muscle relaxants for the management of acute low back pain. P T. 2014;39(6):427-435. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25050056.

- 9.Ghanavatian S, Derian A. statpearls. October 2019. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526037/.

- 10.Freynhagen R, Busche P, Konrad C, Balkenohl M. [Effectiveness and time to onset of pregabalin in patients with neuropathic pain]. Schmerz. 2006;20(4):285-288, 290-292. doi:10.1007/s00482-005-0449-0

- 11.Derry S, Wiffen P, Kalso E, et al. Topical analgesics for acute and chronic pain in adults – an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;5:CD008609. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008609.pub2

- 12.Gates M, Hartling L, Shulhan-Kilroy J, et al. Digital Technology Distraction for Acute Pain in Children: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics. January 2020:e20191139. doi:10.1542/peds.2019-1139

Reviewing with the Staff

The ED is a painful place for patients, between long waits, non-ergnomic chairs and crowding, it can be difficult to get comfortable. Think about pain as one of those initial vital signs and do what you can to comfort and ease patients. Remember, most of us got into this to try and help people, to be healers, and providing compassion and comfort are essential parts of that service. My first step is to always consider what I can do in addition to medications, can I provide solace, help a patient reposition, is there some way to distract them?

For most pain, starting with a combination of acetaminophen and a nsaid (assuming no contraindications) is a safe place to start and actually demonstrates similar efficacy to opioids for MSK complaints. For patients who need to be NPO, consider if an NSAID (like ketorlac) can be used; for renal colic it has been shown to be superior to opioids.

The opioid crisis has really changed the lens through which we view pain. Whereas initially opioids were touted as a panacea, we are now aware of their addictive potential and that they cause hyperalgesia and worse death. They are directly responsible for truncated lifespans and a generation of lost souls. It led to an early change in my practice to be more cognizant of the real risk of outpatient pain medications. Studies have shown that if individuals leave the ED with a narcotic script, they have an increased risk of overdose and opioid dependence. This became at odds with my desire of healing - if we can’t ‘cure’ pain then how do we move forward? This reminds us how important the conversation is with patients. Now when considering outpatient analgesia, I screen using the ORT, I walk patients through the pyramid and talk about the risks and benefits of different classes, I assess how their pain has been controlled in the ED and consider how severe their ailment is and consider potential interactions with home medications. Pain control requires an individualized approach.