The wave of baby boomers is coming to an ED near you and it’s time to get prepared [1]. ED overcrowding does not seem to be going away anytime soon, and anything we can do to get these patients back to the community is better for everyone.

While not all 80 year olds have multiple medical problems (we have a spectrum bias based on what we see at work) it does not take many geriatric patients to add significantly to our already busy ED workload. The ED is a focal point for access to the health care system for all patients, particularly the elderly, so we need to prepare ourselves better for their needs. With this in mind, there is a movement towards developing a ‘Geriatric ED’ based on population trends and studies that found implementing geriatric friendly strategies successfully reduced the admission rate of geriatric patients [2].

Currently, few ED’s are lucky enough to have a Geriatric ED or even physicians with geriatric expertise within their group. However, excellent training is available online (see Geri-EM.com) that covers the major issues facing geriatric patients in the ED. Additionally, there are usually an excellent array of services for these patients in your community; you just need to know how to access them! It does not take much for certain geriatric patients to fall below the threshold of dependence, and by using the strategies outlined in this post we might be able to get them back to their home.

The Approach to Geriatric Patients in the ED

The overall approach to the geriatric patient must include the functional, social, cognitive, and medical domains [3].

[bg_faq_start]a) Functional assessment

A functional assessment evaluates the patients ability to complete activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental ADLs (iADLS). ADLs are the things you do in the first 20 mins of your day (transferring, toileting, bathing, dressing, feeding, and continence) while iADLs are the things you learned to do when you left to go off to university (meals, housecleaning, meds, finances, driving/transport, shopping, phone/technology).

[bg_faq_end][bg_faq_start]b) Social assessment:

A social assessment focuses on their supports in the community. A good way to assess this is to ask ”If something bad happened, who would you call?”

[bg_faq_end][bg_faq_start]c) Cognitive assessment

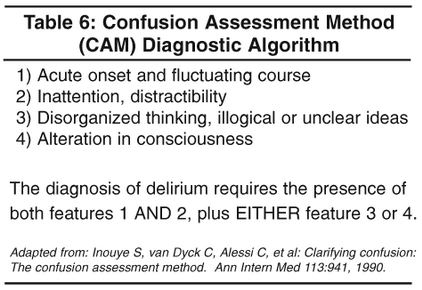

A cognitive assessment includes screens for Delirium (CAM) & Dementia (mini-Cog). The mini-Cog can be done quickly and should be a vital sign for a Geriatric patient. If it is abnormal, it should prompt further assessment with a mini-mental exam.

[bg_faq_end][bg_faq_start]

d) Medical assessment

The physical assessment is something that we already do pretty well. It quantifies the reason for their presentation: Why did they faint? What was injured when they fell? etc. We could probably do a better job of checking their medications for appropriateness and interactions, but realistically we often don’t have the time for this in the confines of an ED visit. A topic most certainly worthy of another Boring EM post!

[bg_faq_end]Specific Scenarios

There are also some specific situations which we need to be aware of that require additional assessment in the geriatric patient:

[bg_faq_start]a) Does your patient have impaired mobility?

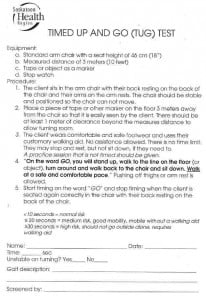

Often geriatric patients can have impaired mobility after a minor injury or flare of arthritis. Consider performing a “Timed Up and Go” or TUG Test [4]. This test is performed as outlined below and gives you a sense of whether or not a patient requires a mobility aid. If they do, physical therapy (PT) can often see them in the ED and make the necessary arrangements. If they will be discharged and require help at home for a couple of days, an appointment with a community PT for follow-up and mobility aid teaching can often be set up for them at their residence. If larger concerns are identified the community PT can refer them for a Geriatric Assessment.

[bg_faq_end][bg_faq_start]

b) Is your patient at risk for falls?

Effective decision tools have been developed by Carpenter and Tiedeman [5,6] to predict falls in the elderly. (Editor’s note: For some more #FOAMed on geriatric fall assessment, be sure to check out The SGEM Episode #89: Preventing Falling to Pieces where Dr. Milne reviews Dr. Carpenter’s latest meta-analysis on the topic with him as a guest!)

Carpenter [5]:

Tiedeman [6]:

If your patient screens positive for as a fall risk, community occupational therapy (OT) can go to their home and see what improvements can be made for reducing their risk (ie shower bars, bath seats, removal of throw rugs, etc.). If larger concerns are identified, community OT can refer them for a Geriatric Assessment.

[bg_faq_end][bg_faq_start]c) Does your patient have complex geriatric issues?

Patients with multiple medications, dementia, fall risk, etc who do not require admission need referral for a geriatric assessment. Prior to consult, they can often send someone to their home to collect information and to collect their medical records. A full geriatric assessment might include assessment by OT, PT, social work, nursing, physician +/- geriatric psychiatry, pharmacy, recreational therapy, and a dietician.

[bg_faq_end][bg_faq_start]d) Can future medical events be prevented?

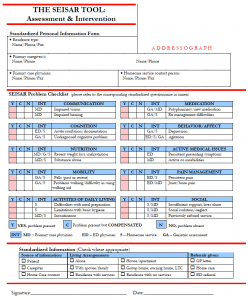

Prevention is the future of the geriatric ED. Tools are being developed to identify seniors who are at risk (the ISAR questionnaire [7]) and determine appropriate interventions (SEISAR [8]):

A score of 2 or higher on the ISAR questionnaire suggests need for intervention and prompts further assessment with the SEISAR (Systemic Evaluation & Intervention for SRs at Risk) Tool [8] to see which interventions would be of benefit.

As these assessments are quite in depth, they would require more than just a home care coordinator. Dedicated individuals are needed for these types of geriatric assessment. I suspect that resources for these types of services will increasingly be made available as our population continues to age.

[bg_faq_end]Conclusion

The ED’s geriatric population is going to continue to increase. This population has unique needs that historically, have not been well addressed in the ED. This post outlined a basic approach for the assessment of geriatric patients and some common scenarios that emergency physicians should be prepared to address with evidence-based resources. Emergency medicine trainees and attendings that familiarize themselves with these resources will be better prepared to address the unique needs of our geriatric patients.

Edited / Reviewed by Brent Thoma (@Brent_Thoma)

[bg_faq_start]References

- Foot, D. K., & Stoffman, D. (1997). Boom bust and echo: how to profit from the coming demographic shift (1st Edition). Saint Anthony Messenger Press and Franciscan.

- Keyes, D. C., Singal, B., Kropf, C. W., & Fisk, A. (2014). Impact of a new senior emergency department on emergency department recidivism, rate of hospital admission, and hospital length of stay. Annals of emergency medicine, 63(5), 517-524.

- Retrieved from Geri-EM.com September 8th, 2014.

- Bohannon, R. W. (2006). Reference Values for the Timed Up and Go Test: A Descriptive Meta‐Analysis. Journal of geriatric physical therapy, 29(2), 64-68.

- Carpenter, C. R., Scheatzle, M. D., D’Antonio, J. A., Ricci, P. T., & Coben, J. H. (2009). Identification of fall risk factors in older adult emergency department patients. Academic emergency medicine, 16(3), 211-219.

- Tiedemann, A., Sherrington, C., Orr, T., Hallen, J., Lewis, D., Kelly, A., … & Close, J. C. (2012). Identifying older people at high risk of future falls: development and validation of a screening tool for use in emergency departments. Emergency medicine journal, emermed-2012.

- Dendukuri, N., McCusker, J., & Belzile, E. (2004). The identification of seniors at risk screening tool: further evidence of concurrent and predictive validity.Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 52(2), 290-296.

- Retrieved from http://stmarysresearch.ca/en/publications_and_tools/clinical_tools/isar-seisar December 28, 2014