Cohen is an 8-year old boy (right hand dominant) who fell from the monkey bars and sustained a closed, angulated left distal radius fracture. He is neurovascularly intact and has normal vital signs for his age. He weighs 30kg. He is in a moderate amount of pain despite Tylenol and Advil which was administered in the ED. You note that he will need further pain management, reduction and splinting of his forearm injury in the ED.

The latest review of the TREKK series discusses procedural sedation in pediatric patients.1

What are some considerations associated with pediatric procedural sedation?

Developmental

- Age appropriate distraction and explanation

- Family presence in the room is key* as children are often fearful in the pre-sedation period, distraction techniques should be utilized, allowing a family member to stay at the bedside/ in the room while the child is being sedated and while the procedure is occurring2

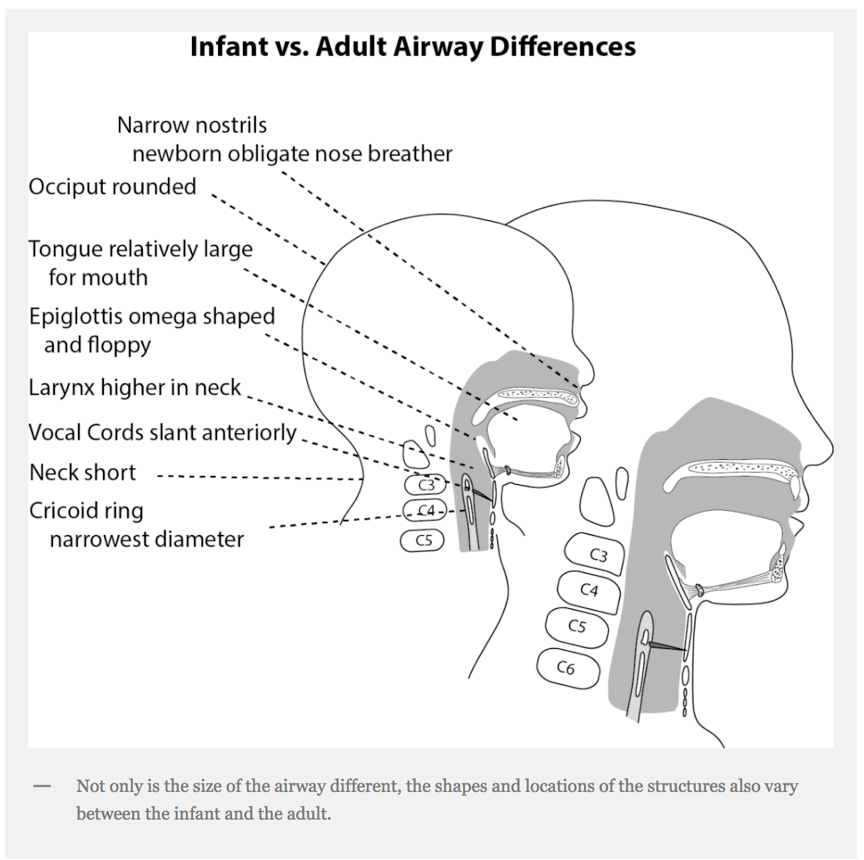

Airway

Image adopted from Dr. Christine Whitten’s FOAMed post “Intubating the Toddler or Infant”. https://airwayjedi.com/2016/04/18/intubating-the-infant-or-toddler/#more-1087

[bg_faq_start]What are the guidelines on pre-procedural fasting? Does procedural sedation of a pediatric emergency department patient need to be delayed based on NPO?

There are no absolute guidelines regarding the duration of pre-procedural fasting. The literature regarding whether adherence to ASA fasting guidelines is needed to maintain patient safety is not clear. 3 The ACEP 2013 clinical policy on procedural sedation gives a level B recommendation on not delaying procedural sedation in adults or pediatric ER patients based on fasting time.4 The American Society of Anesthesiologists Practice Guidelines in 2011 recommends waiting 2 hours for clear liquids, 6 hours for light meals and 8 hours in other cases before elective procedures requiring general anesthesia, regional anesthesia, or sedation/ analgesia.5

[bg_faq_end]Key points in avoiding adverse events in pediatric sedations:

- Where possible, have one provider responsible only for managing the sedation and airway, and one provider to perform the procedure

- Use a specific sedation record and checklist

- Administer weight-based dosing of medications

- Monitor patients for depth of sedation

- Know or have available pediatric age-appropriate vital signs

- Have equipment (see below), skill, and personnel to detect/ rescue patients from events such as oxygen saturation, apnea, laryngospasm

- Use capnography if patient was pre-oxygenated and/or direct visualization of the chest wall is not possible

What should be present and set up prior to your procedural sedation:

- Suction

- Cardiovascular monitoring including cardiac leads and BP, pulse oximetry

- Airway equipment (laryngoscope blades of varying size, ETTs with stylets, supraglottic devices (LMA, king LT), OPA, NPA, ETCO2 capnography*, syringes, securing device/tape

- Means of PPV- BVM + peep valve

- IV equipment

- Oxygen supply, nasal prongs, face mask

- Resuscitative medications (PALS)

- Intubation medications (analgesic/sedative/hypnotic , paralytic,)

- Defibrillator

*Capnography: ACEP’s policy suggests this is a level B recommendation, where capnography may be used as an adjunct to pulse oximetry and clinical assessment to detect hypoventilation and apnea earlier than pulse oximetry and/or clinical assessment alone in patients undergoing procedural sedation and analgesia in the ED.2

[bg_faq_end]What are some different scenerios in which you may consider procedural sedation in the ED?

Non-painful procedures (ie diagnostic imaging)

THE GOAL: to control the patient’s movements

*Distraction techniques should always be attempted before and during medications are administered

2. Minor painful procedures (laceration repair, dental extraction)

THE GOAL: anxiolysis and moderate analgesia.

3. Major painful procedures (orthopedic reductions, complex laceration repair)

THE GOAL: profound analgesia and motion control.

Laryngospasm

Laryngospasm refers to the closure of the true vocal cords, resulting in a potentially life-threatening partial or complete airway obstruction. It has been observed that prior to laryngospasm, one may hear a high pitched inspiratory stridorous noise, which is followed by complete airway obstruction.

A 1990 meta-analysis of 97 studies with > 11 thousand children, Green and colleagues reported a laryngospasm rate at 0.4% in ketamine sedations.6 In most of these cases, the laryngospasm was short-lived and responded to oxygenation/ PPV. Two children required intubation for laryngospasm.

[bg_faq_start]

How do you manage the laryngospasm?7

- Stop the procedure

- Call for help

- Administer 100% O2 through a tight-sealed BVM and apply PPV to force the cords open (CPAP)

- Use ‘Larsons Notch’ by applying painful inward and anterior pressure bilaterally while performing a jaw thrust

- Prepare intubation equipment for potentially difficult airway

- Deepen the sedation/ anesthesia (propofol at 0.5mg/kg IV push)

- If hypoxia persists despite deepening anesthesia, consider administering paralytic (succinylcholine 1.5 mg/kg or rocuronium 1.2 mg/kg) and then progress to intubation

Image from Larson’s original paper, reproduced by LITFL #FOAMED Medical Education Resources7

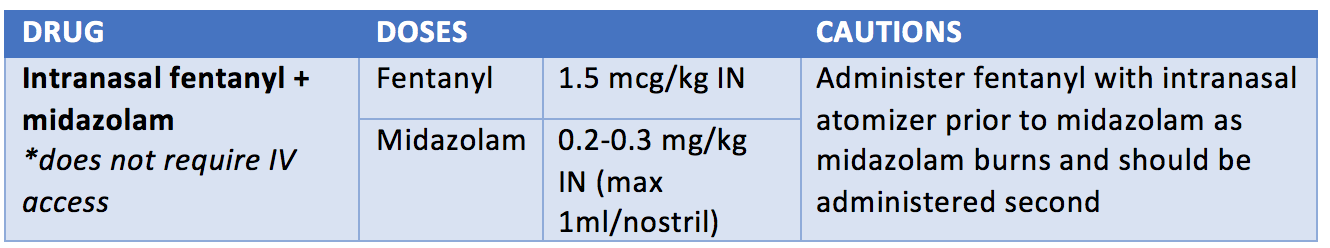

[bg_faq_end][bg_faq_start]What are some tips for using intranasal fentanyl?

The general rule to dosing intranasal fentanyl is using twice the dose you would use for IV fentanyl5. A recommended IN dose is 1-2 mcg/kg (max of 100mcg), which onsets in about 2-3 minutes. To counsel the child in taking this medication intranasally, you can instruct them to take a deep breath in “like smelling a flower”.8 A volume of maximum 1 ml should be used in each nare.5 If the child is congested, you should avoid intranasal medications as absorption will decrease and dosing may be unreliable.

[bg_faq_end]Post sedation care

A patient should be monitored in the ED until they are back to being able to perform their baseline activities (developmentally appropriate, such as walking), in addition to tolerating oral intake.

Back to the Case

Cohen required procedural sedation for reduction of his left distal radius fracture. He was moved into a resuscitation room, and the Pediatric emergency resident explained to Cohen and his parents the need for using an agent (Ketamine) to relax and dissociate Cohen for the reduction. They were encouraged to stay present in the room to comfort Cohen prior to any medication administration. The respiratory therapist was present, and Cohen was hooked up to cardiac and respiratory monitors with end tidal CO2 monitoring. An IV was initiated. It was ensured that all appropriate-sized airway equipment was present and checked in the room. A syringe with 45 mg (1.5mg/kg x 30 kg) of ketamine was drawn up and administered slowly until Cohen was sedated, his forearm fracture reduced, and casted. The family was discharged home approximately 1 hour later, after Cohen was speaking, had drank some juice without vomiting, and could ambulate.

References

Reviewing with the Staff

This case highlights key considerations when sedating a child in need of a procedure that is painful and/or requires them to remain still. ED Procedural sedation for children is most commonly performed to facilitate fracture reductions, but complex laceration repair, abscess incision and drainage, foreign body removal and lumbar puncture are other common indications. While serious adverse events and need for significant intervention (eg. positive pressure ventilation) are uncommon in ED procedural sedation in children, physicians must be prepared to recognize and manage complications such as apnea, laryngospasm and airway obstruction.

A thorough pre-sedation assessment that includes the patient\'s medical history, allergies, medication use, NPO status, airway, and vital signs will help physicians determine whether a child may be safely sedated in the ED. Patients with important risk factors for major complications (ASA ≥ III, age < 1 month, history of obstructive sleep apnea, sedation for endoscopy/bronchoscopy) may not be appropriate for ED sedation and anesthesia should be consulted. Understanding a patient’s risk profile will help the sedating physician anticipate potential complications or adverse events that may occur during the sedation. Medication choice should be guided by need for analgesia and depth of sedation, keeping in mind the patient's inherent risk factors and the physician's comfort and familiarity with the adverse events associated with the chosen medication. Having personnel who are comfortable recognizing and managing adverse events associated with one-level of sedation deeper than targeted, close patient monitoring, age-appropriate rescue equipment and using weight-based dosing for sedation medications are essential and contribute to making the sedation as safe as possible. Documentation of administered medications, vital signs and patient's responses is should be documented for the medical record. Patients should be monitored until they return to baseline activities and have tolerated some oral intake.

Adherence to preprocedural fasting guidelines is highly variable in pediatric ED sedation. There have been no reported cases of pulmonary aspiration in children undergoing ED procedural sedation. Further, several pediatric ED cohorts have shown no association between fasting duration and the occurrence of any type of adverse event.

The bottom line is that procedural sedation is safe and effective in healthy children undergoing short procedures in the ED. To ensure the safest sedation practitioners should be knowledgeable and prepared.