Survival outcomes from cardiac arrest remain poor despite recent advancements in resuscitation science and education. The delivery of high quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) during cardiac arrest is a key component of clinical care. The delivery of high quality CPR is associated with improved survival outcomes. Unfortunately, many studies have demonstrated that providers consistent struggle to provide guideline compliant CPR during cardiac arrest care1,2.

The formula for survival in cardiac arrest outlines three key components that contribute to survival outcomes: medical science, educational efficiency, and local implementation3. Various research groups have explored different strategies to improve CPR delivery during cardiac arrest. Educational strategies such as distributed CPR training and just-in-time (JIT) workplace-based training have demonstrated improved performance in skills sessions4,5,6, but results do not consistently translate to improved performance in the clinical environment. In a recent study conducted by our research group, JIT trained providers demonstrated 38% chest compression (CC) depth compliance in comparison to 13% CC depth compliance in non-JIT trained providers during a simulated cardiac arrest case7. The use of CPR feedback devices during patient care resulted in 33% CC depth compliance; while a combination of JIT training and use of a CPR feedback device during resuscitation improved CC depth compliance to 48%7. Clearly, other factors are at play. Why aren’t providers consistently delivering guideline compliant CPR even when they have just received refresher training AND are receiving real-time feedback during the resuscitation?

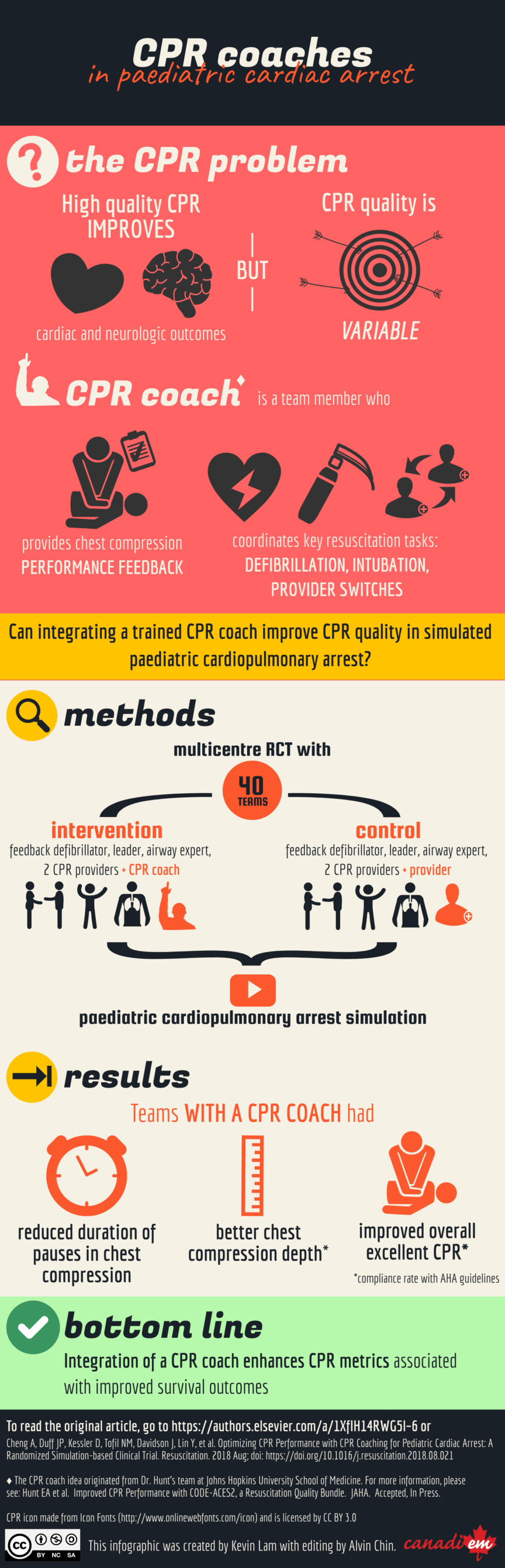

The research group at Johns Hopkins University led by Dr. Elizabeth Hunt noticed that teams who were focused on delivering high quality CPR were then more likely to miss the underlying causes of the arrest, i.e. it was difficult for the Resuscitation Leader to manage both the Basic and Advance Life Support components of the arrest. Her research team can up with a new resuscitation team role – the CPR Coach – tasked with providing real-time performance feedback to improve CPR quality during cardiac arrest8. Of note, once a CPR feedback defibrillator was available to provide information regarding the quality of care, one would think a CPR Coach would not be necessary. However, despite receiving visual (and sometimes verbal) feedback from the defibrillator, during both real and simulated cardiac arrests, providers would often stray from guidelines while providing CC. Some were distracted by other team members, others lost focus on the task at hand, while others questioned the accuracy of the device. The goal of the CPR coach is to ensure that the compressor will provide deliver exquisite CPR, compliant with the AHA guidelines and to cognitively unload the Resuscitation Leader such that they can focus on following the Advanced Life Support algorithm and diagnosing and treating the underlying cause.

To determine the impact of the CPR Coach role, we conducted a simulation-based, randomized controlled trial by recruiting practicing ER and PICU providers across four pediatric institutions. All CPR Coaches were trained in a standardized fashion using a repetitive practice model of simulation-based training. The CPR Coach role was carefully designed to maximize impact on key variables known to improve survival from cardiac arrest, namely: improved CC depth and rate, improved chest compression fraction, and reduced pre, post and peri-shock pause duration. In this study, BOTH the control and CPR Coach teams used a CPR feedback defibrillator during the simulated cardiac arrest case. While we anticipated a positive outcome, we were surprised to see the magnitude of effect imparted by integrating a CPR Coach into the resuscitation team (70% CC depth compliance in CPR Coached teams). Reflecting on these results, we can clearly see how a CPR Coach helps with the local implementation element of the formula for survival; helping providers translate their CPR skills from practice sessions into the clinical environment.

We are in the midst of planning a multicenter clinical trial to determine if the CPR Coach role improves survival outcomes in real cardiac arrest patients. In the interim, we would love to hear what you think! Would a CPR Coach work in your institution? What benefits would you forsee? What barriers would you need to overcome to make this happen?