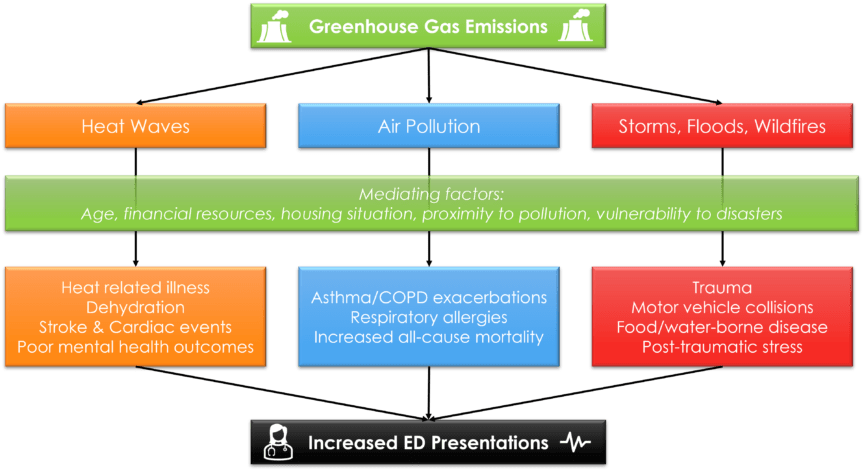

This two-part series will address the bidirectional relationship between EM and climate change. Part 1 will explore heat waves, atmospheric pollution, and natural disasters as illustrative examples of the impact of climate change on the ED. Beyond these examples, climate change also impacts other health issues such as water quality, infectious disease and food security (Figure 1).1,2 Part 2 will discuss the reciprocal impacts of emergency medicine practice on climate change, as well as steps emergency physicians can take to reduce their environmental impact, at a personal and systems level.

In September 2021, 257 medical journals joined together in a call to action on climate change, describing it as “the greatest threat to global public health.”3 We currently stand at a pivotal timepoint. The climate has warmed 1.2 degrees Celsius since pre-industrial times, the past seven years have been the hottest on record, and average temperatures are projected to increase by an additional 2.4 degrees by 2100.1 While the COVID-19 pandemic increased awareness of the impacts of climate change and caused greenhouse emissions to temporarily fall, pandemic recovery is predicted to lead to a rebound increase in emissions of over 5%.1 Between 2030-2050, climate change’s effects such as heat stress, infectious disease and malnutrition are conservatively projected to cause 250,000 excess yearly deaths.1,4

Unfortunately, the negative impacts of climate change on health are concentrated in vulnerable populations. This includes children, the elderly, and those suffering from social inequities, both in Canada and across the globe.1,5 For example, children are highly susceptible to gastrointestinal disease; seniors’ comorbidities and decreased reserve make them more vulnerable to extreme temperatures and poor air quality.5,6 Additionally, people of lower socioeconomic status are more likely to inhabit areas that are flood-prone, affected by heavy pollution, have poor access to sanitation and drinking water, all of which may put them at risk of becoming homeless.5,6 Emergency medicine (EM), as a front-line specialty which disproportionately serves vulnerable populations, will be highly affected by these threats.5,7

Heat Waves

The record-breaking Pacific heat wave this summer, which killed 570 people in British Columbia (BC) alone, brought the impacts of climate change uncomfortably close to home.1,8 The director of the BC Centre for Disease Control called it the “most deadly weather event in Canadian history” and directly attributed it to anthropogenic climate change.8

Heat waves increase morbidity and mortality through environmental illnesses such as heat stroke and dehydration.5,7 They are also associated with increased presentations to the ED for other physical illnesses, including ischemic heart disease and stroke, presyncope, dehydration and renal failure.6,9 The physiological mechanisms for these relationships are complex and not fully elucidated. Cardiac impacts are thought to be associated with heat-related strain on the thermoregulation system which causes vasodilation, inflammation, coagulopathy and changes in heart and respiratory rate.6 Heat events also worsen mental health. In their 2021 climate change report, The Lancet found there was a 155% increase in negative expressions on Twitter during the 2020 heatwaves compared to the 2015-2019 average. Rates of suicidality and violence are also reported to be significantly increased during extreme heat events.1,9

Given these impacts, emergency physicians should therefore be aware of the dangers of extreme heat events and counsel patients on heat avoidance and proper hydration. There may also be opportunities to advocate for hospital-level changes like increased staffing during high-risk periods, and air-conditioned cooldown areas for those without access to climate control within their homes.

Air Pollution

Ambient air pollutants are currently linked to 3.3 million global yearly deaths, and their atmospheric levels continue to rise.2 In North America, most pollutants, including ozone, nitrogen oxides, methane, and fine particulate matter, are formed by fossil fuel combustion in vehicles and power plants.2,10 The warming temperature and decreased precipitation is also increasing the frequency of wildfires, which can increase nearby air pollutant levels by a factor of 10.2

Airborne pollutants have diverse respiratory consequences. For example, ozone is a pulmonary irritant which directly contributes to increased ED visits for COPD and asthma exacerbations.5,10 By contrast, fine particulate matter deposits in the alveoli, and is associated with increases in all-cause mortality.2,10 Warmer temperatures and increased atmospheric CO2 may also increase the volume and spread of pollen, boosting the number of ED visits for asthma and allergic rhinitis.10

While emergency physicians are experts in managing acute respiratory conditions, these impacts will exacerbate the already high demands placed on EDs across the country.

Storms, Floods and Wildfires

Greenhouse gas emissions trap heat within the natural environment, increasing the frequency and severity of extreme weather events.2 Over the course of 6 months in 2020, 84 disasters such as floods, droughts and storms affected 51.6 million people worldwide who were already impacted by COVID-19.1 In the coming years, the increasing incidence of natural disasters will likely cause more mass-casualty events,1,2 which are primarily managed by pre-hospital and emergency medicine.

The effects of natural disasters on emergency medicine are numerous. Initial hazards include trauma from storm-related debris, drowning and hypothermia from floods, and wildfire-related burns.5,9 There is also the potential for direct damage to hospital buildings, as well as power and supply chains.5 This can quickly overwhelm local EDs, precluding them from managing their own patient populations.5 As patients are isolated or forced to evacuate, there are also increases in motor vehicle collisions, food and water-borne diseases, and exacerbations of chronic disease due to decreased access to medications and primary care.5 Finally, after the event is resolved, patients may experience post-traumatic stress related to their experiences.5,9

Emergency medicine physicians can play a key role in preparing for these events by encouraging their hospitals and broader communities to assess their local risks of specific natural disasters, and implement disaster management and surge capacity plans.2

Conclusion

The growing climate crisis is already profoundly impacting emergency departments across Canada. We have only discussed a few direct health risks, but many more exist.1,2,9 This situation will continue to worsen in the coming years. Additionally, malnutrition and childhood exposure to pollution will likely increase susceptibility to chronic disease, increasing ED presentations in the long term.2,10 Part two of this series will address the ways in which emergency medicine practice harms the environment, and how we can find opportunities for improvement.

This post was copyedited by Rhiannan Pinnell (@PinnellRhiannan)

References

- 1.Romanello M, McGushin A, Di N, et al. The 2021 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: code red for a healthy future. Lancet. 2021;398(10311):1619-1662. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01787-6

- 2.Haines A, Ebi K. The Imperative for Climate Action to Protect Health. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(3):263-273. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1807873

- 3.Atwoli L, H B, Benfield T, et al. Call for emergency action to limit global temperature increases, restore biodiversity and protect health. BMJ Open. 2021;11(9):e056565. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056565

- 4.World Health Organization. Quantitative Risk Assessment of the Effects of Climate Change on Selected Causes of Death, 2030s and 2050s. World Health Organization; 2014:0-128. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241507691

- 5.Sorensen C, Salas R, Rublee C, et al. Clinical Implications of Climate Change on US Emergency Medicine: Challenges and Opportunities. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;76(2):168-178. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.03.010

- 6.Basu R, Pearson D, Malig B, Broadwin R, Green R. The effect of high ambient temperature on emergency room visits. Epidemiology. 2012;23(6):813-820. doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e31826b7f97

- 7.Hess J, Heilpern K, Davis T, Frumkin H. Climate change and emergency medicine: impacts and opportunities. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(8):782-794. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00469.x

- 8.Gomez M. June heat wave was the deadliest weather event in Canadian history, experts say. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/ubcm-heat-dome-panel-1.6189061. Published October 2, 2021.

- 9.Rocque R, Beaudoin C, Ndjaboue R, et al. Health effects of climate change: an overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Open. 2021;11(6):e046333. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046333

- 10.Joshi M, Goraya H, Joshi A, Bartter T. Climate change and respiratory diseases: a 2020 perspective. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2020;26(2):119-127. doi:10.1097/MCP.0000000000000656

Reviewing with the Staff

While the effects of climate change have been slowly slipping their way into our daily practice as emergency physicians for years, the increasing frequency of extreme weather events in Canada is something we can no longer ignore. From extreme heat causing heat stroke, to flooding and fires causing mass displacement and increased mental distress, to wildfire smoke causing a significant uptick in reactive airways exacerbations, we are seeing direct examples of the effects of climate change in the faces of our patients, and disproportionately in the faces of our most vulnerable patients.

Climate change is, and will be, the great health emergency of our time, and it is our responsibility as carers for the most vulnerable to answer the call of duty to mitigate the effects of climate change to protect our patients.