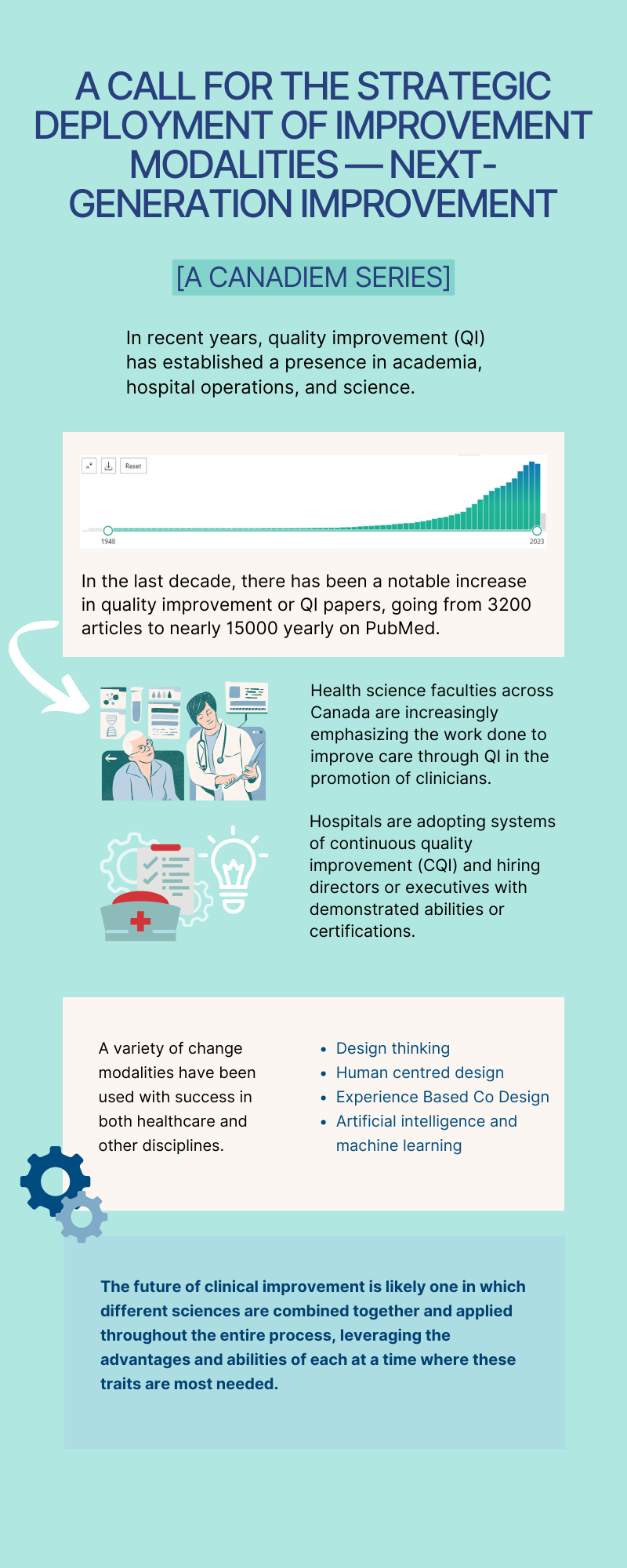

Quality Improvement (QI) is in the middle of a “market surge”. Over the last few years, we have seen QI move from being a fad to having an established presence in academia, hospital operations, and science. A plot of Pubmed articles with the search criteria “quality improvement” OR “QI” yield a very flat slope between 1948 and 2009 (Figure 1). Since then, there has been a notable increase, going from 3200 articles to nearly 15000 yearly in the last decade.1 Faculties of Health Sciences throughout Canada continue to emphasize the work done to improve care through QI in the promotion of clinicians. Hospitals are also beginning to adopt systems of continuous quality improvement (CQI) and hiring directors or executives who have demonstrated abilities or certifications in QI. This increasing relevance, emphasis, and investment can no longer be overlooked.

Yet it remains peculiar that QI has achieved this type of broad adoption, at a cadence not often associated with knowledge adoption horizons. Research in the traditional sense, is often thought to be a viscous and rigid process. It has been estimated that it takes approximately 17 years for healthcare research evidence to translate into changes in clinical practice.2 QI research, on the contrary, is viewed as a more nimble and iterative process, allowing for more efficient uptake and reactivity to change. This peculiarity is not because QI was recognized as a pragmatic method of systematically and scientifically addressing problems. Instead, the peculiarity lies in why QI was chosen as the fundamental currency of pragmatic change in healthcare. Doubtless, organizations such as the Institute for Healthcare Improvement have been deeply influential in adopting QI as we currently know it.3 Perhaps its relative similarity to clinical research, by using well-known tools and leaning on measurable data, has made it “just different enough” to allow for a favorable assessment of value and potential. Moving away from these factors and taking the science on its merits of process (or product) improvement alone, our predilection for QI is less easily explained.

A variety of change modalities have been used with success in both healthcare and other disciplines. For example, methods such as Design Thinking and Human Centered Design are well described when applied to developing innovative product and process solutions.4 Internationally, the National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom has adopted a model called Experience Based Co-Design (EBCD) to partner with patients on solutions.5 As technology advances, healthcare challenges are being approached using Artificial Intelligence (AI) or Machine Learning (ML) as potential change modalities. AI and ML solutions have been successfully applied to the clinical space using improvement modalities, such as QI and Design to understand use cases and implement with iterative evaluation.

What is most remarkable is that, in a sector with almost unparalleled process complexity that is widely acknowledged by those who work in it, we seem to have a need to identify a singular modality which is likely to deliver extensive dividends of improvement. The idea quite simply is wishful thinking. Whilst disciples of each improvement modality are relatively adept at describing the limitations of others, it may be that all the Clinical Improvement Sciences (yes this is a new term — coined here!) have applications in which they shine and others in which they would be misapplied.6 Being an exclusive strong disciple of a single improvement modality is shirking the potential of other improvement modalities and the synergy of combining methods of each based on the specific need. In essence, the improvement modality (or combination) selected are based on the constraints and realities of the problem which is to be solved.

And therein lies the future of improvement. An array of techniques, approaches and philosophies in which the next healthcare problem is dropped, to be consumed by the most suitable combination of Clinical Improvement Sciences. Health systems that invest in understanding the full gamut of clinical improvement sciences, beyond QI and clinical research, will be better set up with the necessary tools for more thorough and rapid change. The future of clinical improvement is likely one in which different sciences are combined and applied throughout the entire process, leveraging the advantages and abilities of each at a time where these tools are most needed.

The distillate in all of the clinical improvement sciences is to understand the problem, from all of its angles. The tools deployed to get from that point to an effective solution are different. They likely all work given the correct problem — the idea of subgroups here should not be foreign to us. In some problems, several approaches may be independently effective. Yet what is clear is that health systems that use a variety of approaches are likely to solve more complex problems. Academic centers need to value clinical scholarship (scholarship of engagement) rather than singular improvement modalities.7Publishing avenues need to be created for all of the clinical improvement sciences. Perhaps most topically, all of the people looking to improve healthcare, under any modality, need to realize they have more in common than they know or like to admit.

In summary, QI modalities have had a rapid uptake in healthcare over the past decade. Many change modalities exist with no ‘one size fits all’. QI practitioners will benefit from understanding different modalities, their benefits and limitations, in order to use clinical improvement sciences to their full potential.

In the following series, we will juxtapose some of the established ones, and explore some of the newer improvement modalities that may make up the armamentarium of the clinical improvement sciences. Join us for our next post.

This post was copy edited by Benson Law and Mackenzie MacAuley.

Senior Editors: Ahmed Taher

References

- 1.National Library of Medicine (US). (Quality improvement) OR (QI) – Search results – PubMed. PubMed. Published 2024. Accessed 2024. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=%28Quality+Improvement%29+OR+%28QI%29&filter=years.2014-2024

- 2.Grant J, Green L, Mason B. Basic research and health: a reassessment of the scientific basis for the support of biomedical science. Res Eval. Published online December 1, 2003:217-224. doi:10.3152/147154403781776618

- 3.Sampath B, Rakover J, Baldoza K, Mate K, Lenoci-Edwards J, Barker P. Whole System Quality: A Unified Approach to Building Responsive, Resilient Health Care Systems. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Published 2012. Accessed 2024. https://www.ihi.org/sites/default/files/IHI-Whole-System-Quality-White-Paper.pdf

- 4.Beckman SL, Barry M. Innovation as a Learning Process: Embedding Design Thinking. California Management Review. Published online October 2007:25-56. doi:10.2307/41166415

- 5.The Point of Care Foundation. EBCD: Experience-based co-design toolkit. The Point of Care Foundation. Published 2012. https://www.pointofcarefoundation.org.uk/resource/experience-based-co-design-ebcd-toolkit/

- 6.Mondoux S, Shojania KG. Evidence‐based medicine: A cornerstone for clinical care but not for quality improvement. Evaluation Clinical Practice. Published online April 11, 2019:363-368. doi:10.1111/jep.13135

- 7.Boyer EL. The Scholarship of Engagement. The Scholarships of Engagement. Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Published 1996. Accessed 2024. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3824459