You are working in an inner city emergency department (ED) and you notice that there are 10 patients who are waiting for their COVID-19 test results. You know that these patients are all experiencing homelessness but you have no idea if they were all exposed at one place, what symptoms they’re experiencing, and how best to inform your local public health department. You create a spreadsheet to start keeping track of these details during your shift but realize that it cannot be a sustainable long-term solution.

The above clinical scenario described the situation at St. Michael’s Hospital, part of Unity Health Toronto, in the spring of 2020. Dr. Carolyn Snider, Chief of Emergency Medicine, recognized the need for a tool to help take care of a highly vulnerable patient population and approached Unity Health Toronto’s Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA) team to begin working on a health informatics implementation in the middle of a crisis. In today’s post, we’ll go over the first part of a multi-step process in designing and developing a dashboard to solve a real-world clinical and QI challenge. This first post covers problem identification, team building, and identifying metrics that both quantify the problem and how well it is being addressed.

What’s the problem?

“Everyone has to have a lens of deployment even when they start talking about the problem on day 1… instead of taking it as an afterthought” — Dr. Sebnem Kuzulugil (Director of Data Integration and Governance, Data Science and Advanced Analytics, Unity Health Toronto)

There’s a famous adage attributed to Albert Einstein that if he was given one hour to solve a problem, he would spend 59 minutes defining the problem and 1 minute resolving it. Although this statement contains hyperbole, there is evidence in a wide number of fields, including information technology, that more energy spent up front in the problem identification and design phases will save time, money, and effort later on in the project. Research by McKinsey and Company, a management consulting firm, and the University of Oxford found that unclear objectives and a lack of business focus were responsible for roughly one-third of information technology projects that run over budget and deliver less value than intended.1 These are outcomes that can be harmful to organizations, especially for hospitals that are already stretched thin during a pandemic! At Intercom, a software-as-a-service company that provides tools for businesses to chat with their customers, the Chief Product Officer challenges Product Managers to spend 40% of their time on identifying and defining problems before even beginning to design any solutions.2

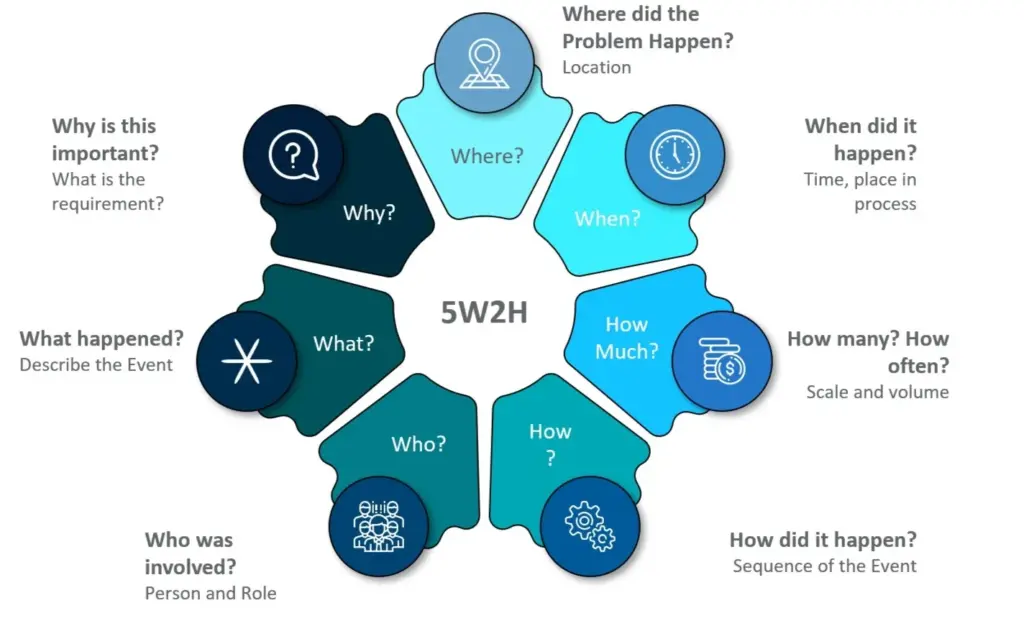

Clinicians are often well-poised to identify problems due to their front-line experience, especially in the ED. Problems often fall into four key categories: patient and provider safety, flow, patient and provider care experience, and patient care outcomes. In different clinical environments, there are nuances within these four categories due to inherent differences in workflows and ultimately the care being delivered. Flow on an inpatient general internal medicine (GIM) ward is fundamentally different than flow in an ED since patients spend, on average, much more time on the GIM ward. At Unity Health, a key driver of project success is that problems are brought forward by clinicians and decision-makers to the DSAA team. Tools covered in our previous post on root cause analysis, such as fishbone diagrams and process mapping, as well as the 5W2H tool are helpful in working towards a clear, crisp problem statement.

If you want to go far, go together

Delivering the best care to patients in hospitals requires interdisciplinary effort, and more often than not, a dashboard will be used by many different stakeholders at once. With respect to the COVID-19 and homelessness dashboard, the end solution would be used by emergency department physicians, nurses, social workers, senior decision-makers, and community partners. A key tenet of human-centered design is to understand end-users and bring them on board at the beginning of the process! End users may have slightly different understandings of the problem and thus slightly different needs for a solution.

In addition to key representatives from different stakeholder groups and the information technology team that actually builds the solution, it may also be beneficial to look for individuals with the following roles to enable problem definition and downstream tasks such as implementation. Clinical champions can help obtain buy-in from prospective end-users and resource investment from executives.3,4 A project manager keeps the entire project on track by managing resources (including people and their time), overseeing task prioritization and completion, foreseeing and eliminating blockers, and creating up-to-date documentation.5 In our next post, we will outline some tools that are especially useful for clinical champions and project managers navigating the development and deployment of a dashboard.

KPIs, OKRs, and ROI – oh my!

“Key performance indicators” (KPIs) and “objectives and key results” (OKRs) are very similar to the “SMART goals” used in motivational interviewing. KPIs are similar to outcome measures in QI. KPIs are the data elements captured on the dashboard. In our example, they might include things like: how many patients experiencing COVID-19 and homelessness are in the ED each day, the number of shelters with identified outbreaks each week, or the daily proportion of social work assessments that are conducted within a pre-specified amount of time.

OKRs are an approach to goal-setting that has been the foundation of the management methodology at Netflix, Google, and many other leading technology companies.6 As the name suggests, OKRs have two components: the objective (the “what”) and the key results (the “how”). OKRs are complementary to KPIs in that they provide strategic direction towards a goal that KPIs can help measure. OKRs are meant to be inspirational and challenging, but also feasible. An example of an OKR for this case is as follows:

OBJECTIVE: Provide sentinel surveillance of outbreaks in shelters for the local public health unit.

KR1: All COVID-19 patients experiencing homelessness will have a detailed social work assessment within 3 hours of entering the ED to identify possible shelters with outbreaks.

KR2: Team “X” at the local public health unit will receive a brief email report of which shelters may have outbreaks every 48 hours.

Having a clearly defined problem statement followed by KPIs and OKRs that are actionable can help ensure that your dashboard ensures a return on investment (ROI). OKRs are reviewed on an ongoing basis, such as monthly or quarterly, depending on the nature of the goal being set.

“The tools you build… need to have the endpoints in them and people supporting them to make them actionable.” – Dr. Alun Ackery (Medical Director of Informatics and Technology, Unity Health Toronto)

Wrap Up

After speaking to fellow ED physicians as well as colleagues in nursing, social work, and community services you decide that a dashboard could help everyone take better care of COVID-19 patients who are experiencing homelessness. You have scheduled a meeting with representatives from these different groups to define a clear problem statement, KPIs, and OKRs that you’ll take to the hospital IT team to see if they’re able to help.

That’s it for our first post in our series about designing and deploying dashboards. We hope this gave you a good overview of problem identification, team building, and the importance of KPIs and OKRs in ensuring ROI. Let us know what you think on Twitter at @Hi_Qui_Ps. If there is anything specific you would like to learn about, e-mail us at [email protected]. Stay tuned for our next post on how to go about designing your dashboard!

Senior Editor: @shawn-mondeux

This post was copyedited by Sydney Terry.

- 1.Bloch M, Blumberg S, Laartz J. Delivering Large-Scale IT Projects on Time, on Budget, and on Value. McKinsey & Company ; 2012. Accessed October 2022. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/delivering-large-scale-it-projects-on-time-on-budget-and-on-value

- 2.Adams P. Great PMs don’t spend their time on solutions. Intercom. Accessed October 2022. https://www.intercom.com/blog/great-product-managers-dont-spend-time-on-solutions/

- 3.Gui X, Chen Y, Zhou X, Reynolds T, Zheng K, Hanauer D. Physician champions’ perspectives and practices on electronic health records implementation: challenges and strategies. JAMIA Open. 2020;3(1):53-61. doi:10.1093/jamiaopen/ooz051

- 4.Soo S, Berta W, Baker G. Role of champions in the implementation of patient safety practice change. Healthc Q. 2009;12 Spec No Patient:123-128. doi:10.12927/hcq.2009.20979

- 5.Project Management Institute . Who are Project Managers and What Do They Do? PMI. Accessed October 2022. https://www.pmi.org/about/learn-about-pmi/who-are-project-managers

- 6.Panchadsaram R, Prince S. Why use OKRs? I Have Goals. What Matters. Accessed October 2022. https://www.whatmatters.com/faqs/do-i-need-okrs-goals

Reviewing with the Staff

Dr. Mondoux is the Quality and Safety Lead of the Emergency Department at St. Joesph\'s Healthcare Hamilton (SJHH). He is also the Physician Innovation Lead for SJHH.