Arya Stark, a 19-year-old young woman, was violently stabbed in her abdomen with a knife while walking through Braavos. Arya flees, tumbling into the river that flows through the town. She manages to crawl out of the river, but is too exhausted to move further and is clutching her abdomen, curled up on the bank until a helpful passerby realized she was in trouble. Arya was quickly loaded into a horse-drawn cart and brought to the ED. Although it took her three hours to get to the ED by horse, she arrives to triage and is quickly escorted to the trauma bay.

As you walk into the trauma bay, you see a thin young woman who is pale, but remarkably alert given her multiple penetrating abdominal wounds. Noting that Arya is hemodynamically stable with normal vital signs, you proceed with a quick history. Arya explains that she is otherwise well, on no medications other than the occasional herbal supplement common in her time, and has never had any surgery before. She is remarkably stoic as she describes the events that transpired earlier that day. While going for a casual stroll through Braavos, a known enemy to Arya, “the Waif”, stabbed her with a knife multiple times in the right side of her abdomen. Arya grabbed the nearest horse and rushed to the hospital as quickly as she could, but due to the cobblestone roads and crowded streets, it has been almost three hours since the injury. She denies any other symptoms, including hematuria or hematemesis.

On physical exam, you note multiple entrance wounds on Arya’s RUQ, RLQ, and right flank with no through-and-through injuries. Her abdomen is tender and there is significant ecchymosis in the right flank. She shows some voluntary guarding on palpation of the right side of her abdomen. You are shocked that Arya is still alert with stable vital signs. She insists she is fine and should return to Braavos, but you tell her it is important for her to have some imaging done.

Background

Kidneys are generally well-protected organs, located in the retroperitoneum and guarded by ribs, muscles of the back, and perinephric fat.1. The majority of penetrating renal injuries are caused by stabbings and gunshots.2 A penetrating injury to the abdomen has great potential to cause damage to the kidneys and their associated structures, including renal vessels and the kidney’s collecting system (tubules, ducts, calyxes, and ureter). There is also a very high correlation between renal injury and injury to other structures outside of the genitourinary system, with one study finding an association of up to 86%,3 so investigating concomitant injuries of nearby organs and vessels is of utmost importance.

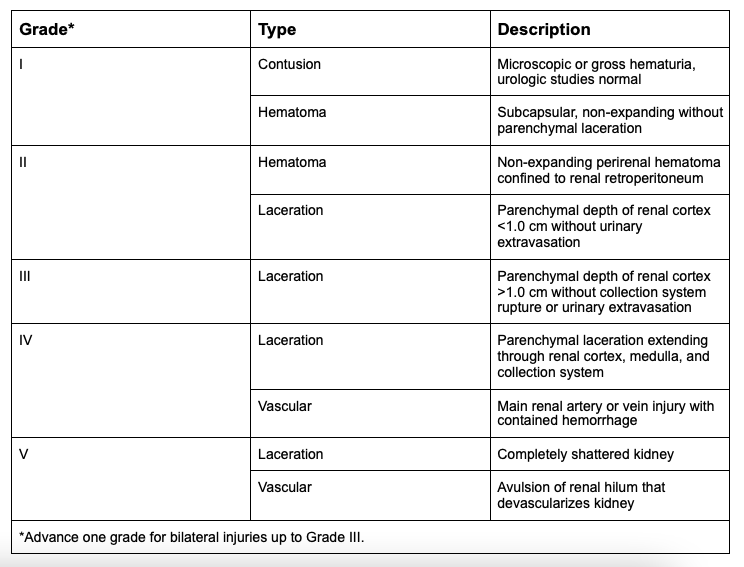

Kidney injuries can be classified based on the kidney injury severity score described by the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) (see Figure 1 and Image 1). Higher grades, penetrating mechanism of injury, increasing injury severity, and hemodynamic instability are predictors of the need for nephrectomy.4

Figure 1: Organ Injury Severity Score for Kidneys. 5,6

Image 1: AAST renal injury score7

What is the basic clinical approach to penetrating renal injuries?

Because most penetrating renal injuries occur by stabbing or shooting, the clinical approach begins with the primary survey and secondary survey as per ATLS. Next, obtaining a thorough SAMPLE history, including mechanism of injury, as well as a patient’s Tetanus status, will establish your preliminary suspicion for a penetrative injury. Specifically, ask for any hematuria and pre-existing renal disease or abnormalities. Previous renal diseases, including solitary kidney, renal cysts, and hydronephrosis can complicate outcomes and should specifically be noted. While FAST scans are now established adjuncts of the primary and secondary survey, note that they can be negative in a patient with isolated kidney and retroperitoneal injury.

What investigations should we order?

Labs

In a patient with suspected renal injury, hemoglobin, creatinine, and urinalysis should be ordered urgently.8 Crossmatch/type and screen are also useful in patients who are hemodynamically unstable and require transfusion.

Imaging

All penetrating injuries warrant imaging.9 If unsure of the exact mechanism of injury, any degree of hematuria further warrants imaging, however, the absence of hematuria does not rule out renal trauma as vasculature can be injured.10 Most trauma patients coming through the emergency department will undergo a CT scan. The gold standard for the assessment of kidneys is CT with contrast, both immediate and delayed (also known as CT pyelography). In the emergency department, CT pyelography is often ordered after kidney injury is found on the initial CT scan.

Findings indicating renal injury on CT include the presence of a subcapsular hematoma, perirenal hematoma, parenchymal laceration, and/or urine leak from renal pelvis or collecting system injury.9 While active bleeding indicated by contrast extravasation on CT is not directly a factor in determining AAST grade, its presence can lead to failure of conservative management.9

Although FAST scans are commonly used in the ED and have great utility, due to ultrasound’s low sensitivity of 22% in picking up renal injuries,11 a negative FAST scan does not exclude the need for CT.

What does Urology do for patients with penetrating renal injuries?

Indications for surgical exploration include hemodynamic instability, lack of response to fluid resuscitation, or AAST grade 5 vascular injury.8 If there is high suspicion for a urine leak then surgical exploration is further indicated as a perinephric drain or ureteric stenting may be needed.8

Hemodynamically stable patients with suspected renal injuries are often managed conservatively. This approach has been shown to lead to lower rates of nephrectomy. More specifically, all grade 1, 2, and 3 injuries (based on the AAST grading system-see Figure 1), independent of mechanism, should be managed conservatively.8 At some centers, grade 4 injuries are also being treated conservatively, with the recommendation to obtain repeat imaging within 48 hours to identify and manage developing complications.8

Approach to Unstable Retroperitoneal Bleeds

Angiographic embolization is another option if the hemorrhage is easily localized.12 At some centers, the majority of renal traumatic hemorrhages are managed with angiographic embolization performed by interventional radiology.13There have been very few complications with this approach,14 and it results in preserved renal function and parenchyma.15 It is generally used for injuries of AAST Grade I, II, III, or IV, however, a small retrospective study has found percutaneous embolization of hemorrhage in hemodynamically stable Grade V renal injury in patients successful in controlling the hemorrhage 100% of the time.16

Back to the Case

Arya still has not voided, so you are unsure about the presence of any hematuria. Luckily for her, she has arrived at a modern ED and there is imaging available. The CT scan shows that the knife penetrated through her abdomen, and nicked some superficial blood vessels, but avoided all major vessels including the renal artery. It managed to avoid all other major structures and organs.

Due to Arya’s stable vitals and level of alertness, you decide she is hemodynamically stable. You order a CBC, type and screen, urinalysis, and, after ensuring she has no allergies to contrast, an urgent CT pyelogram.

You call the interventional radiologist on call, who books her for urgent angiographic embolization. In the meantime, you watch Arya’s vitals closely to ensure that she remains hemodynamically stable.

Main points:

- Penetrating renal injuries are often associated with other intra-abdominal injuries.17

- Approach: hemodynamic stability, physical exam, imaging, urology referral

- Key findings on clinical exam: mechanism of injury (stabbing or gunshot),2 hemodynamic instability (not always), hematuria (56% of cases).17 Ecchymosis, flank tenderness, displaced lower rib fractures.

- Imaging of choice: CT with contrast immediate and delayed phases (CT pyelography). Any degree of hematuria warrants imaging, however an absence does not rule out renal trauma as vasculature can be injured with no hematuria.10 All penetrating injuries warrant imaging. Although FAST scans are commonly used in the ED and have great utility, due to ultrasound’s low sensitivity of 22% in picking up renal injuries,11 a negative FAST scan does not exclude the need for CT.

- Differentiating injury to parenchyma of kidney vs vessels vs collecting system (including tubules, ducts, calyxes)

- Organ injury scale for kidney by AAST

- Some patients may require nephrectomy, however conservative management has been demonstrated to be a feasible option.18,19

This case was copy-edited and uploaded by Fadi Bahodi and Rhiannan Pinnell (@PinnellRhiannan). Be sure to check out previous Game of Thrones Case Reports on topics including neck trauma, penetrating chest trauma, pregnancy and trauma, toxin-induced cardiac arrest, and hypothermia/cardiac arrest.

References

- 1.Lee Y, Oh S, Rha S, Byun J. Renal trauma. Radiol Clin North Am. 2007;45(3):581-592, ix. doi:10.1016/j.rcl.2007.04.004

- 2.Santucci R, McAninch J. Grade IV renal injuries: evaluation, treatment, and outcome. World J Surg. 2001;25(12):1565-1572. doi:10.1007/s00268-001-0151-z

- 3.Voelzke B, Leddy L. The epidemiology of renal trauma. Transl Androl Urol. 2014;3(2):143-149. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2223-4683.2014.04.11

- 4.Davis K, Reed R, Santaniello J, et al. Predictors of the need for nephrectomy after renal trauma. J Trauma. 2006;60(1):164-169; discussion 169-70. doi:10.1097/01.ta.0000199924.39736.36

- 5.Kozar R, Crandall M, Shanmuganathan K, et al. Organ injury scaling 2018 update: Spleen, liver, and kidney. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;85(6):1119-1122. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000002058

- 6.The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. Injury Scoring Scales. The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. https://www.aast.org/resources-detail/injury-scoring-scale#kidney

- 7.Anselmo da Costa I, Amend B, Stenzl A, Bedke J. Contemporary management of acute kidney trauma. Journal of Acute Disease. Published online January 2016:29-36. doi:10.1016/j.joad.2015.08.003

- 8.Patel KM, Nuttall MC. Genitourinary trauma. Surgery (Oxford). Published online July 2019:404-412. doi:10.1016/j.mpsur.2019.04.006

- 9.Chong S, Cherry-Bukowiec J, Willatt J, Kielar A. Renal trauma: imaging evaluation and implications for clinical management. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2016;41(8):1565-1579. doi:10.1007/s00261-016-0731-x

- 10.Alonso R, Nacenta S, Martinez P, Guerrero A, Fuentes C. Kidney in danger: CT findings of blunt and penetrating renal trauma. Radiographics. 2009;29(7):2033-2053. doi:10.1148/rg.297095071

- 11.Smith J, Kenney P. Imaging of renal trauma. Radiol Clin North Am. 2003;41(5):1019-1035. doi:10.1016/s0033-8389(03)00075-7

- 12.Muller A, Rouvière O. Renal artery embolization-indications, technical approaches and outcomes. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2015;11(5):288-301. doi:10.1038/nrneph.2014.231

- 13.Aldiwani M, Georgiades F, Omar I, et al. Traumatic renal injury in a UK major trauma centre – current management strategies and the role of early re-imaging. BJU Int. Published online March 23, 2019. doi:10.1111/bju.14752

- 14.Stewart A, Brewer M, Daley B, Klein F, Kim E. Intermediate-term follow-up of patients treated with percutaneous embolization for grade 5 blunt renal trauma. J Trauma. 2010;69(2):468-470. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e3181e5407a

- 15.Chatziioannou A, Brountzos E, Primetis E, et al. Effects of superselective embolization for renal vascular injuries on renal parenchyma and function. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2004;28(2):201-206. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2004.05.003

- 16.Brewer M, Strnad B, Daley B, et al. Percutaneous embolization for the management of grade 5 renal trauma in hemodynamically unstable patients: initial experience. J Urol. 2009;181(4):1737-1741. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2008.11.100

- 17.Kansas B, Eddy M, Mydlo J, Uzzo R. Incidence and management of penetrating renal trauma in patients with multiorgan injury: extended experience at an inner city trauma center. J Urol. 2004;172(4 Pt 1):1355-1360. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000138532.40285.44

- 18.El H, Nederpelt C, Kongkaewpaisan N, et al. Contemporary management of penetrating renal trauma – A national analysis. Injury. 2020;51(1):32-38. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2019.09.006

- 19.Raza S, Xu P, Barnes J, et al. Outcomes of renal salvage for penetrating renal trauma: a single institution experience. Can J Urol. 2018;25(3):9323-9327. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29900820

Reviewing with the Staff

Once again Tessa has done a fantastic job of reviewing the subject of penetrating renal trauma. It falls under the general domain of renal trauma. The most common mechanism for renal injury is blunt trauma (predominantly by motor vehicle accidents and falls), while penetrating trauma (mainly caused by firearms and stab wound) comprise the rest. The mainstay of renal trauma diagnosis is based on contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT), which is indicated in all stable patients with gross hematuria, and in patients presenting with microscopic hematuria and any systolic blood pressure reading less than 90. Additionally, CT should be performed when the mechanism of injury or physical examination findings are suggestive of renal injury (e.g. rapid deceleration, rib fractures, flank ecchymosis, and every penetrating injury of the abdomen, flank or lower chest). It should be clear that hemodynamic instability may not allow the diagnostic use of a CT.

Management of renal trauma today requires a multidisciplinary approach, involving Interventional Radiology, Trauma (General) Surgery, and of course Urology. The management has evolved during the last decades, with a distinct evolution toward a nonoperative approach. Most renal trauma patients are managed nonoperatively with careful monitoring, reimaging when there is any deterioration, and the preferred use of minimally invasive procedures. These procedures include angioembolization in cases of active bleeding, and endourological stenting in cases of urine extravasation.

The long term goal of renal trauma management is renal preservation if at all possible, as they are non-replaceable. So remember, England does not have a kidney bank… but they do have a Liverpool.