This updated episode of CRACKCast covers Rosen’s Chapter 27 (9th Ed.) regarding gastrointestinal bleeding. With this review we hope to streamline your approach to patient’s losing their circulatory volume from their GI tract to avoid the bloody mess. Thank you to Saskatoon EM residents Dr. Sey Shwetz and Dr. Josh Butcher for joining us for this episode!

Shownotes – PDF Here

[bg_faq_start]Rosen’s in Perspective

Ahhhhh, the GI bleed; a problem that is as old as time. Some of medicine’s most interesting stories stem from discoveries around this pathology. And while we have all met the patient with black stools, we may have not all experienced the full spectrum of illness that this pathology can create. If you are still junior (or just verrrrrry lucky), you may have not yet seen how “down with the sickness” these patients can be. In fact, the mortality rate for UGI bleeds is not insignificant, weighing in at a whopping 15%. The scary thing is, despite the myriad of advancements made in intensive care, endoscopy, and surgery, the mortality rate for UGI bleeds has not budged for decades. LGI bleeds, while less lethal, still carry significant risk for death (4%). I know, yikes.

For those of you who worry that the next hypotensive GI bleed to walk through your ED doors will strain your knowledge, have no fear – CRACKCast is here. Today’s episode will give you all of the information you will need to handle that case like the boss you are! First, we will go about speaking to the anatomic definitions you need to know to differentiate between UGI and LGI bleeds. After that, we will cover an approach to the history, physical exam, and ancillary testing strategies that you can use on your next shift. We will next review Rosen’s algorithm on the initial stabilization of these patients. Last, we end the episode with those classic quick snappers you have all come to love that you can stow away in the back of your mind until it comes time to crush your next on-shift quiz.

[bg_faq_end]Core Questions:

[bg_faq_start][1] Define upper gastrointestinal versus lower gastrointestinal bleeding and differentiate between the two based on anatomic location

Alright, everyone. We are strapping on our medical school hats today with this one.

Upper GI bleeding is defined as bleeding from a source within the GIT that is located above the ligament of Treitz. What is the ligament of Treitz, you ask? Well, perhaps it is more helpful to know the name that anatomists actually call it – the suspensory muscle of the duodenum. This structure connects the duodenum, jejunum, and duodenojejunal flexure to the connective tissues surrounding the superior mesenteric artery and celiac artery. It marks the transition zone between the upper and lower GI tracts. Conversely, lower GI bleeding is defined as bleeding from a source within the GIT that is located below the ligament of Treitz.

This anatomic distinction is important as it affects the clinical signs and symptoms associated with upper and lower GI bleeds. Upper GI bleeds typically present with the patient reporting either frank red or coffee-ground emesis, upper abdominal pain, and melena. The characteristic black colour of the stool is secondary to the presence of hemoglobin that has been altered by digestive enzymes and intestinal bacteria. Alternatively, lower GI bleeds typically present with frank blood per rectum and/or bloody or maroon stools (i.e., hematochezia). The blood released from the lower tract does not experience the degree of exposure to the digestive enzymes we mentioned earlier, so it remains red (…ish).

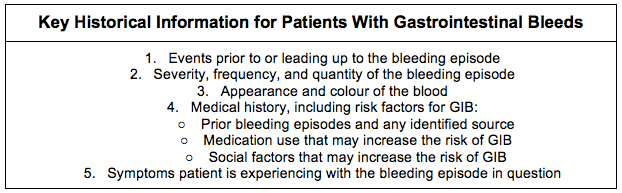

[2] Outline an approach to the history and physical examination for the patient with complaints consistent with GIB. (Box 27.3)

This figure is modelled after Box 27.3 – Key Historical Information for Patients With Gastrointestinal Bleeds (GIB’s) in Rosen’s 9th Edition. Please refer to the text for further details.

[3] List 5 causes of UGI bleeding and 5 causes of LGI bleeding. (Table 27.1)

This figure is modelled after Table 27.1 – Common Causes of Gastrointestinal (GI) Bleeding in Adults and Children in Rosen’s 9th Edition. Please refer to the text for further details.

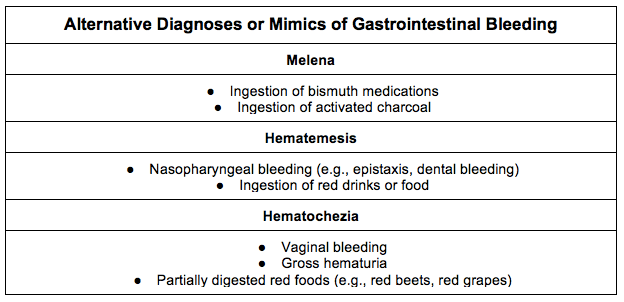

[4] Outline six alternative diagnoses or mimics of GI bleeding. (Box 27.1)

This figure is modelled after Box 27.1 – Alternative Diagnoses or Mimics of Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Rosen’s 9th Edition. Please refer to the text for further details.

[5] List five characteristics of patients with high-risk GI bleeds. (Box 27.2)

This figure is modelled after Box 27.2 – Characteristics of Patients With High-Risk Gastrointestinal Bleeds in Rosen’s 9th Edition. Please refer to the text for further details.

[6] Describe an approach to ancillary testing in the patient with GI bleeding.

[7] List five substances that when ingested, can result in a falsely-positive stool guaiac study

This is one of Rosen’s hidden lists, so we hooked you up with a 10/10 DDL (Dillan’s Distilled List) situation. So, sit back, strap in and get ready.

[8] Outline an approach to the management of the patient with GI bleeding. (Fig 27.3)

This question is modelled after Figure 27.3 – Diagnostic and Management Strategies for Gastrointestinal Bleeding.

Step One: Stable or Unstable

- If unstable:

- Resuscitate, obtain two points of access with large-bore IV’s

- Initiate crystalloid infusion

- Consider transfusion

- If stable, progress to Step Two

Step Two: History, Physical Examination, Ancillary Stories

- If hematemesis, coffee-ground emesis, melena, and other features on exam/testing, treat as UGI bleed

- If hematochezia and other features on exam/testing consistent with LGI bleed, treat as such

Management of Massive UGI Bleed:

- Summary of Management

- Intubate as needed to protect the airway from aspiration of hematemesis

- Emergent GI consult for ED endoscopy

- IV PPI

- If variceal bleed considered:

- Somatostatin analogue

- Ceftriaxone

- Sengstaken-Blakemore Tube placement PRN

- Massive transfusion protocol PRN

Management of Non-massive UGI Bleed

- Summary of Management

- If young (age <60Y), no comorbidities, normal vital signs, no evidence of orthostasis, normal laboratory studies, and reliable patient with prompt outpatient follow-up, consider PPI and discharge following ED observation period

- If risk factors present or previously stable patient becomes unstable, admit to floor versus ICU and get an inpatient GI consult for urgent inpatient endoscopy

Management of Lower GI Bleed

- Summary of Management

- Perform anoscopy

- If the patient has a bleeding source visualized, normal and stable vital signs, no comorbidities, no coagulopathies, and is young (<60Y), discharge from the ED after observation and outpatient follow up is arranged

- If risk factors present or stability changes during observation period, admit to the floor versus ICU and get an inpatient GI consult for urgent inpatient colonoscopy

- Angiography and scintigraphy can be considered by admitting team

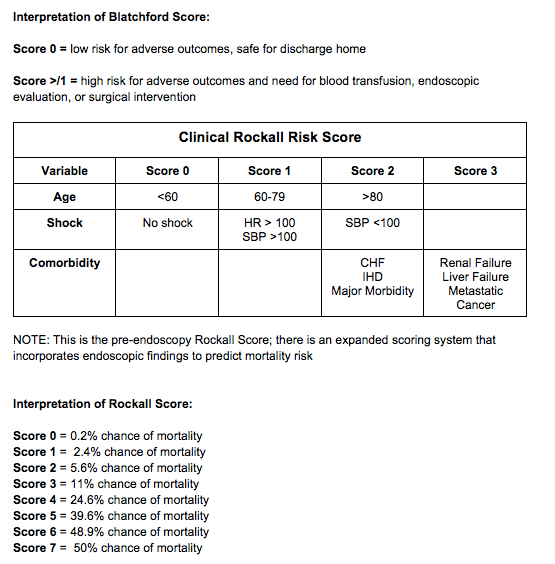

[9] Detail the Blatchford and Clinical Rockall Risk Scores. (Tables 27.3/27.4)

This figure is modeled after Tables 27.3 and 27.4 – Blatchford Score and Clinical Rockall Score in Rosen’s 9th Edition. Please refer to the text for further details.

Wisecracks:

[bg_faq_start][1] Outline the three most common causes of UGIB in pediatric and adult patients.

Answer:

See Table 27.1 in Rosen’s 9th Edition for more information

Pediatric UGI Bleeds: Duodenal ulcers, gastric ulcers, esophagitis, gastric erosion, esophageal varices, MW tear

Adult UGI Bleeds: Peptic ulcers (gastric > duodenal), gastric erosion, esophagogastric varices, MW tear, esophagitis, gastric cancer

[2] Outline the three most common causes of LGIB in pediatric and adult patients.

Answer:

See Table 27.1 in Rosen’s 9th Edition for more information

Pediatric LGI Bleeds: Anorectal fissure, infectious colitis, IBD, juvenile polyps, intussusception, Meckel’s diverticulum

Adult LGI Bleeds: Diverticular disease, angiodysplasia, colitis (infectious, inflammatory, ischemic), anorectal sources, neoplasms, and UGI bleeding

[3] What percentage of patients presenting with hematochezia actually have an UGIB?

Answer:

Up to 14% of bleeds associated with hematochezia are actually secondary to an UGI source. These bleeds are typically quite profound and are associated with higher transfusion rates, surgical interventions, and overall mortality.

[4] What volume of blood loss is needed to produce symptoms of anemia in the patient with an acute/subacute GI bleed?

Answer:

According to Rosen’s 9th Edition, blood loss more than 800 ml will usually result in the onset of weakness, SOB, angina, orthostatic presyncope, confusion, palpitations, and reports of cool extremities. These symptoms become pronounced and severe with greater than 1500 ml of blood loss.

[bg_faq_end]Uploaded and copyedited by Ryan Fyfe-Brown