Clinical vignette

A 45-year-old healthy male, presents to the emergency department (ED) with a one-day history of back pain. The pain started while working out at the gym – he lifted a heavy weight above his head and felt a sudden lower back pain (LBP). The patient describes sharp, burning and stabbing pain in the low back that radiates down the posterior and lateral aspect of the left leg to the dorsum of the foot. He has difficulty finding a comfortable position and his pain increases when sitting. There is no bowel or bladder dysfunction. He has no history of IV drug use and no infectious or constitutional symptoms. Physical examination is limited due to pain. He is given acetaminophen and ibuprofen in the ED for pain control and continues to have significant pain and limited mobility.

Background

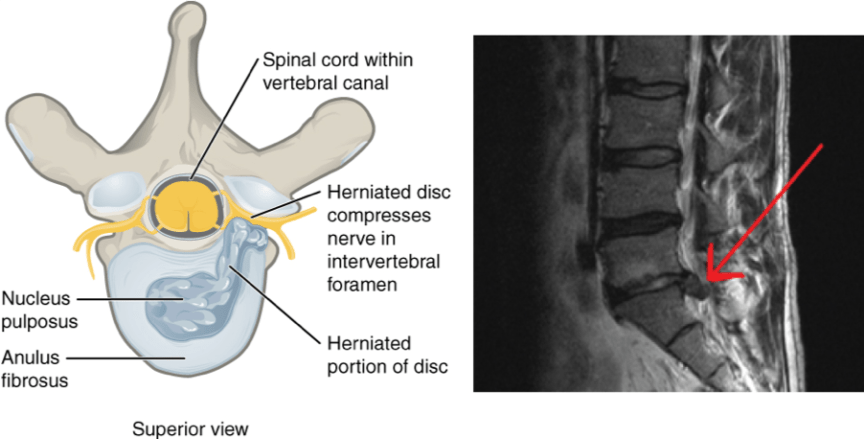

Back pain is the fifth most common presenting complaint in the ED in Canada.1 LBP due to disc herniation (Figure 1) or lumbosacral spondylosis may be associated with radiculopathy and these patients present with considerable pain and limited function.

Once red flags are ruled out, the mainstay treatment in the ED is pain control with acetaminophen and/or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, with consideration given to their side-effect profiles. Non-pharmacological treatment includes heat and/or cold packs and education on good prognosis and avoiding bed rest.2 Early physiotherapy has been shown to reduce future health services utilization, opioid use and need for spinal surgery.3 Despite these treatments, pain and the resultant difficulty to mobilize continue to be barriers to discharge from the ED.4

Evidence for the use of single-dose intravenous corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are used in various inflammatory diseases because they inhibit inflammatory cells and suppress expression of inflammatory mediators.5 They can be delivered systemically (intravenous, intramuscular or oral) or locally to the site of inflammation. Parenteral corticosteroids have been shown to be ineffective in patients with acute non-radicular LBP in the ED.6 In cases of radicular pain, single intramuscular dose7, and tapered oral dosing8 of corticosteroid have not been found to be superior to placebo.

It has been hypothesized that a single intravenous (IV) bolus dose of corticosteroid may be beneficial for patients with radiculopathy.9 The potential advantage is that a higher dose of corticosteroid over a short time period may distribute a greater amount of steroid concentration to the area of herniation.9 Currently only two related randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are available.

A double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial studied the effects of a single dose of 8 mg of IV dexamethasone in addition to standard treatment in ED patients with radicular LBP.4 The study was small (N=58) and the baseline characteristics of the two groups were not similar; the treatment group had a greater visual analog scale (VAS) score compared to the placebo group. The dexamethasone group had a significantly greater reduction in VAS pain scores at 24 hours (1.86 point, 95% CI 0.31 to 3.42, p = 0.0019) and a significantly shorter ED length of stay compared to the placebo group (median hours of 3.5 h vs. 18.8 h, p = 0.049). Once the baseline differences in VAS were controlled with regression analysis, the difference in VAS at 24 hours decreased to 1.33, which was not deemed clinically significant by the authors. There were no significant differences between functional scores or oxycodone requirements between the two groups. However, use of other analgesics such as acetaminophen or NSAIDs were not recorded.

A related RCT (N=65) done outside of the ED had similar findings.9 A single IV bolus of 500 mg of methylprednisolone provided a small and transient but statistically significant improvement in sciatic leg pain during the first three days after treatment (p = 0.04) compared to placebo.9 The corticosteroid group had 5.7 mm (95% CI 0.3-10.9) greater reduction in leg pain VAS compared to the control group on day 1. This benefit lasted approximately two days.9 There was no significant difference in the back pain VAS pain scores between the two groups.

Corticosteroids are associated with a wide range of adverse effects. Both RCTs reported transient side effects in the treatment group that resolved spontaneously. Finckh et al.9 reported that three patients experienced flushing, hypertension or hyperglycemia. Balakrishnamoorthy et al.4 reported that one subject had peri-anal itching immediately after dexamethasone administration. The 500 mg dose of IV methylprednisolone administered by Finckh et al.9 was considerably higher than the typical dose used in other conditions such as COPD exacerbation. Sudden death, cardiac arrhythmias and circulatory collapse have been reported with IV methylprednisolone doses of over 500 mg administered over less than ten minutes.10 Arrhythmias have been reported to occur during or several days after administration of high-dose IV pulse corticosteroids.10 The sample sizes in the above RCTs may be too small to detect some of these rare but potentially dangerous adverse effects of high doses of systemic corticosteroids.

The “bottom” line

The current data does not provide definitive support for the use of a single bolus dose of IV corticosteroid for acute radicular LBP in the ED. Although a small benefit of this treatment was seen in two RCTs, there are concerns regarding the validity of these trials. Additionally the sample sizes of these trials may be too small to detect rare and dangerous adverse effects. Therefore, further studies are needed to establish the efficacy and safety of single-dose IV bolus of corticosteroids for radicular LBP.

Back to the case

After a complete history and physical examination, you diagnose the patient with radicular back pain. Eventually, he notes some improvement in his pain after administration of acetaminophen and ibuprofen. You reassure the patient, and educate him on the sequelae and prognosis of radicular back pain. He is advised to stay active, avoid bed rest and to return to the ED if he experiences any red flags. You provide him with a referral for early physiotherapy and advised him to follow-up with his family doctor for ongoing management.

This post was copyedited and uploaded by Kimberly Vella.

References

- 1.Canadian Institute for Health Information . A Snapshot of Health Care in Canada as Demonstrated by Top 10 Lists, 2011. CIHI (Ottawa, ON); 2012:58.

- 2.Strudwick K, McPhee M, Bell A, Martin-Khan M, Russell T. Review article: Best practice management of low back pain in the emergency department (part 1 of the musculoskeletal injuries rapid review series). Emerg Med Australas. 2018;30(1):18-35. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29232762.

- 3.Arnold E, La B, DaSilva L, Patti M, Goode A, Clewley D. The Effect of Timing of Physical Therapy for Acute Low Back Pain on Health Services Utilization: A Systematic Review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;100(7):1324-1338. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30684490.

- 4.Balakrishnamoorthy R, Horgan I, Perez S, Steele M, Keijzers G. Does a single dose of intravenous dexamethasone reduce Symptoms in Emergency department patients with low Back pain and RAdiculopathy (SEBRA)? A double-blind randomised controlled trial. Emerg Med J. 2015;32(7):525-530. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25122642.

- 5.Barnes P. How corticosteroids control inflammation: Quintiles Prize Lecture 2005. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148(3):245-254. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16604091.

- 6.Friedman B, Holden L, Esses D, et al. Parenteral corticosteroids for Emergency Department patients with non-radicular low back pain. J Emerg Med. 2006;31(4):365-370. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17046475.

- 7.Friedman B, Esses D, Solorzano C, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of single-dose IM corticosteroid for radicular low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(18):E624-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18665021.

- 8.Holve R, Barkan H. Oral steroids in initial treatment of acute sciatica. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21(5):469-474. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18772303.

- 9.Finckh A, Zufferey P, Schurch M, Balagué F, Waldburger M, So A. Short-term efficacy of intravenous pulse glucocorticoids in acute discogenic sciatica. A randomized controlled trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(4):377-381. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16481946.

- 10.Baethge B, Lidsky M, Goldberg J. A study of adverse effects of high-dose intravenous (pulse) methylprednisolone therapy in patients with rheumatic disease. Ann Pharmacother. 1992;26(3):316-320. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1554949.

Reviewing with the Staff

Radicular low back pain is a common reason for patients to come to the ED and a frequent cause of agonizing pain. This pain can be challenging to manage: opioid analgesia has been a mainstay of pain relief in the ED, but the administration of new opioid prescriptions from Emergency Departments have been implicated in the development of opioid use disorder [11]. Parenteral steroids do not seem to be a solution, given the evidence covered above. This leaves emergency physicians in a bind – how can we effectively manage people’s pain while not starting them down a road of opioid addiction? Health Quality Ontario recently developed recommendations for opioid use in acute pain (https://www.hqontario.ca/Evidence-to-Improve-Care/Quality-Standards/View-all-Quality-Standards/Opioid-Prescribing-for-Acute-Pain) and also compiled a collection of resources for prescribers which may be helpful: https://quorum.hqontario.ca/en/Home/Posts/Opioid-Prescribing-for-Acute-Pain-Quality-Standard-Tools-for-implementation

The take-home message from these and other guidelines is to optimize non-opioid analgesia, multi-modal pain treatment, early physical therapy and if a short course of opioids are required, to prescribe a maximum of 3 days duration and 50 mg daily morphine equivalent.