History

A 36-year-old male with no medical conditions was brought to the ED by ambulance after a one-story fall in a workplace parkour incident at the Dunder-Mifflin Paper Company. While it’s debatable if the awkward leapfrogging preceding the incident could be considered parkour, Jim explains that the goal of parkour is “to get from point A to point B as creatively as possible, so technically they are doing parkour as long as point A is delusion and point B is the hospital.” As shocking as his stunt attempt was for someone with only 30 seconds of parkour experience, Andy does tend to have a predilection for odd workplace incidents, like being bear sprayed by colleagues at work or floating away desperately in a sumo suit.

When you ask about the exact mechanism and height of the fall, his coworkers show you their recording, where Andy attempts a jump from about one story, or 14 feet, off a truck, to refrigerators, to dumpster, 360 spin onto the palates, backflip gainer into the trash can, but is unpleasantly surprised when the refrigerator boxes turn out to be empty. He appears to land mainly on his feet, is winded by the impact, and he felt like he hurt his neck when he landed inside the box. When he arrives at the ED, his is complaining of neck pain, low back pain, and left heel pain, but he otherwise seems well and is most notably disrupting the whole ED with a loud falsetto rendition of Kelly Clarkson’s “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.”

Physical exam

On primary survey, the patient is speaking and breathing comfortably, and he is alert and oriented. While assessing his GCS, you say “can you tell me your name?” and he responds “’Nard Dog!”. Michael closes his eyes with a disappointed nod of approval to let you know he’s not wrong. His GCS is 15. His clothing is removed and he is covered with blankets. He has equal air entry bilaterally, no visible chest wall injuries, and O2 saturation of 97%. His skin is well perfused, vitals are stable and there is no obvious bleeding. His ECG shows sinus rhythm with a pulse rate of 80 bpm, his abdomen and pelvis were non tender, and eFAST did not reveal free fluid or pneumothorax.

The secondary survey is largely unremarkable, except for swelling and tenderness over the left heel, and ecchymosis over the sole. He has no neck tenderness on palpation, but is maintained in a C-collar as he continues to complain of neck pain and left heel pain. A CT of the spine, and x-rays of the chest, pelvis and left foot are ordered.

What steps should be taken in the ED?

Discussion

Considerations for triage and injury patterns in falls from height

In Canada, over 40,000 workers are injured annually due to fall accidents.1While it is debatable whether Andy’s fall would be considered occupational, falls were the 3rd most common cause of fatal occupational injuries in 2018 after transportation incidents and violence.2 Another important etiology of falls from height is suicide attempts.3 While the data on fatality rates is inconsistent3,4, there is evidence that the injury patterns are more severe amongst survivors of suicide attempts compared to survivors of unintentional falls from height.3 It is important to have an approach for managing these patients when they arrive in the ED. The general approach to falls from height follows ATLS guidelines for primary and secondary survey. However, knowledge of risk factors for greater severity, and the expected pattern of injuries is helpful.

How should patients be risk stratified?

Patients who fall from height can fall anywhere along the morbidity spectrum from no injuries to severe disability or death. An obvious predictor of mortality is height of the fall.5 Falls from 2 storeys or lower have about a 10% mortality rate or less, while at a height of 4 storeys the mortality rate nears 50%, and falls above 6 storeys are seldom survived.5

Other negative prognostic factors include older or younger age, harder ground, presence of head or chest injuries, and body part first touching the ground (head is most dangerous followed by lateral body surface, anterior body surface, and finally feet).5–7 Therefore, details surrounding the fall such as mechanism, height, and landing should be ascertained in the history if possible in order to help optimize emergency management. In Andy’s case, this is a young adult with no head or chest injuries, who landed on his feet. The only negative prognosticator present is that he landed on hard ground.

What are the most common injury patterns?

The most common injuries after a fall from height tend to be thoracic and lumbar spine fractures, lower limb, pelvic, and upper limb fractures, as well as head injuries, while intraabdominal, aortic, and hollow visceral injuries are less common.8 The most common causes of death in falls from height are traumatic brain injury and exsanguination.3,9,10

Calcaneus fractures

Nearly ¾ of calcaneus fractures are sustained in falls from height, with the majority of those occurring at heights greater than 6 feet.11 Andy fell from a height of approximately 14 ft, landed on his feet, and is complaining of heel pain, all of which should raise suspicion of a calcaneal fracture.

General principles from Rosen’s Emergency Medicine on calcaneal fractures are reviewed here.12 Initial imaging should include foot radiographs with an AP view (to evaluate the calcaneocuboid joint and anterosuperior calcaneus), a lateral view (to evaluate the posterior facet and calcaneal body compression) and an axial, or Harris view (to evaluate the calcaneal tuberosity, subtalar, and sustenaculotalar joints). If a fracture is present, it is important to assess whether the subtalar joint is involved, and if there is compression of the posterior facet. Findings are often subtle – if in doubt, and there is clinical suspicion, order a CT of the foot, as fractures may be occult. Generally speaking, non-displaced extraarticular fractures can be managed with casting, while fractures that are open, displaced, involve the joint, or lead to neurovascular compromise require surgery. These decisions should be made in conjunction with an orthopedic surgeon.

Given the mechanism of high-energy axial load injuries, approximately 6% of calcaneal fractures are associated with vertebral fracture.11 Therefore, in patients with a calcaneal fracture after an axial load injury, it is particularly important to rule out a concomitant vertebral injury.

Andy’s calcaneal x-ray returned normal but given the high clinical suspicion, an additional CT of the calcaneus was ordered. Reassuringly, it comes back normal and he is informed that he does not have a calcaneal fracture. He also does not have any tenderness of focal neurological features to suggest a thoracic or lumbar spine injury.

Does a cervical vertebral fracture still need to be considered in this case?

Spinal fractures and C-spine rules

Does he need C-spine imaging?

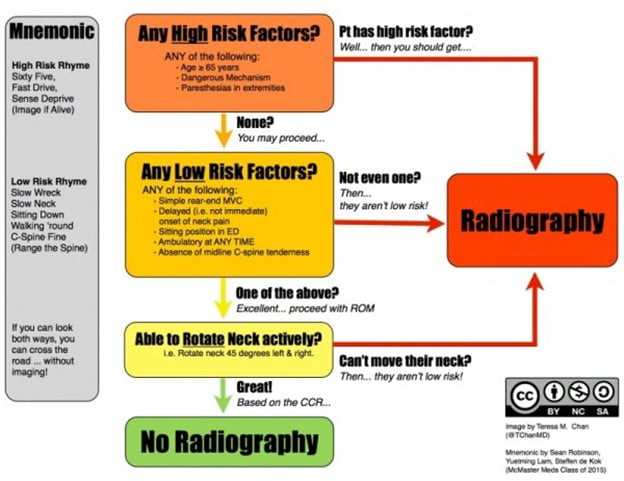

There are two rules to approach whether a C-spine can be cleared without the use of imaging: the NEXUS low-risk criteria and the Canadian C-Spine (CCS) rule. It is important to first understand who these rules should be applied to (ie the “inclusion criteria”). The NEXUS or CCS tools should be applied in patients who had acute blunt trauma to the head or neck, who are stable and alert and who have either neck pain OR no neck pain but meet all of the following criteria: 1) visible injury above the clavicles, 2) are non-ambulatory, and 3) had a dangerous mechanism of injury (fall from >1m). This should not include patients with trivial injuries like facial lacerations. In our case, Andy qualifies for the rule because he sustained blunt trauma to the head or neck, is stable and alert, and has neck pain.

If we apply the NEXUS criteria, patients who meet all of the following 5 criteria are deemed low risk for C-spine injury:

- No posterior midline cervical tenderness

- No focal neurologic deficit

- No evidence of intoxication

- Normal level of alertness

- No painful distracting injuries (as judged by the physician)

In Andy’s case, his heel pain would not be deemed a distracting injury, and he would not require any imaging for C-spine clearance when using the NEXUS criteria provided that he does not have midline cervical tenderness.

However, in a systematic review,13 as well as in an NEJM prospective cohort study that compared the two rules head-to-head,14 the CCS rule had higher sensitivity and specificity than the NEXUS rule, and is thus the preferred decision-making tool. In the head-to-head study, 8,283 patients who qualified for application of the NEXUS and CCS tools as described above (i.e. blunt trauma, stable and alert with neck pain or no neck pain but meeting the 3 criteria) were assessed using both the NEXUS and the CCS rules. For practical reasons, not every patient could receive a CT scan. Thus, the presence or absence of injury was ultimately confirmed by using a CT scan (70% of patients) and the Proxy Outcome Assessment tool (a validated, phone-based questionnaire conducted at 14 days post-injury to rule out C-spine injury; 30% of patients). The CCS was deemed to be more sensitive (99.4% vs. 90.7%) and specific (45.1% vs. 36.8%) than the NEXUS.

Using the Canadian C-Spine rule, Andy, and essentially any individual who qualifies for the rule and sustained a fall from height of ≥1m or 5 stairs, should be sent for radiographic imaging of the C-spine as this would qualify as a dangerous mechanism. Other dangerous mechanisms include axial load to the head, motor vehicle collisions >100km/h or with motorized or passenger ejections, motorized recreational vehicles and bicycle collisions.

Andy was taken for a CT of the C-spine which was negative for any acute pathology. This, in fact, is the most likely outcome as the Canadian C-Spine rule is 100% sensitive but only 42.5% specific. Therefore, you won’t miss a C-spine fracture, but more often than not, patients who are imaged will be cleared.

Do we need to exclude a lower spinal fracture in this patient?

In one study of 188 patients, spinal fractures were the most commonly reported orthopedic injury in falls from height.3 Notably, lumbar spine fractures are most common, followed by thoracic, and then cervical. 8About 1/3 patients who fall from >10 feet suffer spine injuries, where nearly 50% will have multiple injuries at different spinal levels.8 Of these fractures, 63% are lumbar, 25% are thoracic and 12% are cervical. Nearly 10% of patients suffer spinal cord injuries.8 Importantly, the only independent risk factor for spinal fracture is alcohol intoxication – height of the fall does not predict risk; therefore, even in lower height falls, this important diagnosis must be carefully excluded.8 In addition, it is crucial to recognize that 22% of patients with spinal injuries and a reliable clinical exam had no symptoms relating to the spine, though 92% of these patients had distracting injuries.8 Therefore, adherence to spinal precautions, thorough neurological examination, and aggressive evaluation of the spine may be warranted in these patients if you do not plan to image the spine, even if they are asymptomatic.8 In a stable patient who you do not plan to image, examination of the spine should include log-rolling the patient, then palpating the spine to assess for tenderness and step-deformities,15 in addition to an assessment of neurological function by motor and sensory exam of the extremities, and perineal sensation and rectal tone.15

It is important to recognize the high rate of spinal injuries from this mechanism, and have a low index of suspicion. Andy was sent for a CT of his thoracic and lumbar spine, and a minor wedge fracture of the L3 vertebrae was found. In a wedge fracture, the posterior column remains intact, making this a stable injury. However, in severe wedge fractures where ≥50% of vertebral height is lost, or in the setting of multiple adjacent wedge fractures, spinal instability can occur.12 While minor wedge fractures can sometimes be treated in an outpatient setting if there is no neurological deficit present, they frequently require aggressive pain management, and further workup for associated intrathoracic and intraabdominal injuries, and delayed gastrointestinal ileus if this imaging has not already been done.12 Given Andy’s complaint of lumbar spine pain and these imaging findings, he was admitted to hospital for pain management and monitoring.

What else needs to be considered prior to discharge?

After 3 days of monitoring, Andy’s pain is well-controlled and he has not developed any other complications. During the admission of a patient who sustained a fall from height, one should assess whether the cause of the fall was intentional or unintentional. In the case of an intentional fall, a psychiatry consult should be made. For unintentional falls, preventative factors such as workplace safety and management of substance abuse should be considered.

After just a few minutes of history taking, it was deemed that Andy was simply overzealous, which was entirely consistent with his personality and behaviours in other episodes of the show, and he was discharged back to The Office.

Pearls

- Workplace accidents and suicide attempts are common causes of falls from height, and should generally be approached using ATLS guidelines

- Factors like height of the fall, age, surface landed on, and body positioning at landing affect morbidity, mortality and injury pattern

- Vertebral fractures are the most common injury, are frequently asymptomatic, and must be carefully excluded

- If it is appropriate to apply the Canadian C-spine rules, imaging will be recommended due to dangerous mechanism

- Consider psychiatric assessment in intentional falls

This post was copy-edited by @alexsenger.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hunter C. People Are Falling – Statistics Are Not. OHS Canada. https://www.ohscanada.com/overtime/people-are-falling-statistics-are-not/#:~:text=Falls%20happen.,annually%20due%20to%20fall%20accidents.&text=In%20addition%20to%20great%20economic,suffering%20and%20also%20claim%20lives.

- 2.Fatal occupational injuries by event. U.S. Bureau of Labour Statistics. Published 2018. https://www.bls.gov/charts/census-of-fatal-occupational-injuries/fatal-occupational-injuries-by-event-drilldown.htm

- 3.Auñón-Martín I, Doussoux P, Baltasar J, Polentinos-Castro E, Mazzini J, Erasun C. Correlation between pattern and mechanism of injury of free fall. Strategies Trauma Limb Reconstr. 2012;7(3):141-145. doi:10.1007/s11751-012-0142-7

- 4.Spearpoint M, Hopkin C. A model for the evaluation of fatality likelihood associated with falls from heights. Fire Safety Journal. Published online March 2020:102973. doi:10.1016/j.firesaf.2020.102973

- 5.Lapostolle F, Gere C, Borron S, et al. Prognostic factors in victims of falls from height. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(6):1239-1242. doi:10.1097/01.ccm.0000164564.11989.c3

- 6.Turgut K, Sarihan M, Colak C, Güven T, Gür A, Gürbüz S. Falls from height: A retrospective analysis. World J Emerg Med. 2018;9(1):46-50. doi:10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2018.01.007

- 7.Fernandez WG. Trauma: A Comprehensive Emergency Medicine Approach. Academic Emergency Medicine. Published online June 2012:e18-e18. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01369.x

- 8.Velmahos G, Spaniolas K, Alam H, et al. Falls from height: spine, spine, spine! J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203(5):605-611. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.07.002

- 9.Alizo G, Sciarretta J, Gibson S, et al. Fall from heights: does height really matter? Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2018;44(3):411-416. doi:10.1007/s00068-017-0799-1

- 10.Arbes S, Berzlanovich A. Injury pattern in correlation with the height of fatal falls. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2015;127(1-2):57-61. doi:10.1007/s00508-014-0639-9

- 11.Mitchell M, McKinley J, Robinson C. The epidemiology of calcaneal fractures. Foot (Edinb). 2009;19(4):197-200. doi:10.1016/j.foot.2009.05.001

- 12.Walls R, Hockberger R, Gausche-Hill M. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 9th ed. Elsevier; 2017.

- 13.Michaleff Z, Maher C, Verhagen A, Rebbeck T, Lin C. Accuracy of the Canadian C-spine rule and NEXUS to screen for clinically important cervical spine injury in patients following blunt trauma: a systematic review. CMAJ. 2012;184(16):E867-76. doi:10.1503/cmaj.120675

- 14.Stiell I, Clement C, McKnight R, et al. The Canadian C-spine rule versus the NEXUS low-risk criteria in patients with trauma. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(26):2510-2518. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa031375

- 15.Advanced Trauma Life Support: Student Course Manual. 10th ed. American College of Surgeons; 2018.