All the content from the Blood & Clots series can be found here.

CanMEDS Roles addressed: Medical Expert, Collaborator

Case Description

You’re an EM resident seconded off-service on your internal medicine rotation, and it’s your night on call. The emergency physician asks you to see a pregnant patient with acute pulmonary embolism.

Your patient is a 32 year old G3P2 female at 33 weeks gestational age. Her previous pregnancies were uneventful spontaneous vaginal deliveries and she has no prior history of venous thromboembolism (VTE). She presented with chest pain and dyspnea. Heart rate is 102, blood pressure 115/70, oxygen saturation 96% on room air, respiratory rate 22, weight 80 kg.

She has been found to have acute PE in the right middle and upper lobe segmental arteries on ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) scan. She has normal bilateral lower extremity compression ultrasounds. Hb is 98, platelets 156, creatinine 80.

How will you manage her tonight?

Main Text

Question 1: Which anticoagulants can be used safely during pregnancy?

If you feel stressed about managing clots during pregnancy, you are not alone! Deciding how to anticoagulate pregnant patients is challenging as we need to think about both the mom’s health and the teratogenic risks for the baby.

The bottom line is that Warfarin and DOACs for venous thromboembolism (VTE) are contraindicated during pregnancy, and your only options in this situation are heparins (either unfractionated heparin or low molecular weight heparin) 1.

- Vitamin K antagonists (Warfarin) most certainly cross the placenta. Warfarin may cause teratogenicity (particularly in the first trimester), and has been associated with pregnancy loss, fetal bleeding, neurodevelopmental defects, and warfarin embryopathy (nasal hypoplasia, cleft palate, and other anomalies) 2. Warfarin should not be used during pregnancy for the treatment of acute VTE.

- Direct oral anticoagulants (“DOACs” – Dabigatran, Rivaroxaban, Apixaban, Edoxaban) likely cross the placenta, and their effects on the developing fetus are unknown. Pregnant women were excluded from clinical trials evaluating the efficacy and safety of these drugs. So, DOACs should NOT be used during pregnancy as we don’t have enough clinical evidence about whether they lead to bleeding or teratogenicity.

- Heparins – unfractionated heparin (UFH) and low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) – do not cross the placenta and are safe for the fetus. LMWH is preferred over UFH because it has a better safety profile (lower risk of bleeding and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia) 3. LMWH is easier to administer as its syringes come pre-filled and are usually dosed once daily, whereas UFH requires patients to withdraw the desired amount. So, the bottom line is: LMWH is the anticoagulant of choice during pregnancy.

Question 2: Is outpatient treatment with LMWH feasible, and how should it be dosed in pregnancy?

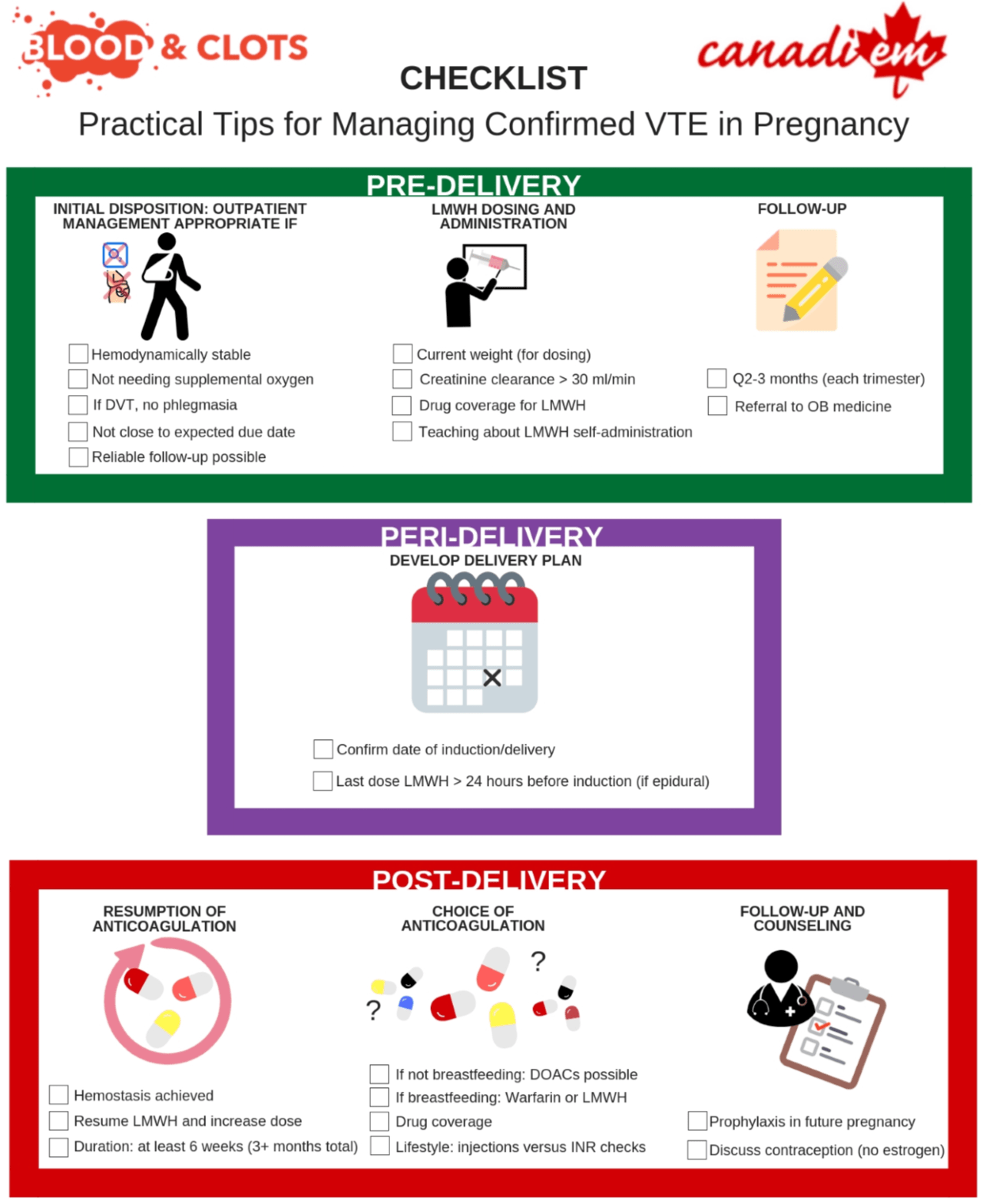

You can consider treating your pregnant patient with acute VTE on an outpatient basis as long as:

- She is hemodynamically stable and has a reassuring oxygen saturation.

- You arrange close follow-up from someone who is able to manage her anticoagulation

- She understands and is able adhere to instructions for when she should seek medical attention again (signs and symptoms of worsening or recurrent VTE)

Choose the initial dose of LMWH based on your patient’s current body weight, not her pre-pregnancy weight. There’s no evidence that one type of LMWH is superior to another.

Table 1: Dosing of LMWH in Pregnancy

| Type of LMWH | Dosing Recommendation 3, 4 | Dose for our patient (80 kg) |

| Enoxaparin | 1 mg/kg every 12 hours, or 1.5 mg/kg once daily | 80 mg SC q12h, or 120 mg SC once daily |

| Dalteparin | 200 units/kg once daily, or 100 units/kg every 12 hours | 15,000 units SC once daily, or 7,500 units SC twice daily* |

| Tinzaparin | 175 units/kg once daily | 14,000 units SC once daily |

*this has been rounded to the nearest pre-filled syringe for patient convenience, as the exact weight-based dose of Dalteparin would be 16,000 units daily. If you want to know the syringe sizes, check out the Ontario Limited Use code website.

We would treat her with Dalteparin 15,000 units SC once daily and teach her to self-inject. It’s important to confirm whether the patient has access to LMWH through private or government-based insurance plans. Some jurisdictions have compassionate programs for LMWH.

She also needs a referral to an obstetrician that manages high-risk pregnancies, and a specialist (e.g. thrombosis specialist, hematologist, or internist) who will assist with managing her anticoagulation during delivery and throughout the remainder of her pregnancy.

Question 3: How long should your patient be treated for? How should anticoagulation be managed in the peri-delivery setting?

[bg_faq_start]In the antepartum (before delivery) period

Pregnant women with acute VTE need therapeutic anticoagulation for a total duration of at least 3 months, and at least 6 weeks of anticoagulation postpartum.

After the first three months some would reduce anticoagulation intensity to an intermediate or prophylaxis dose of LMWH, but we don’t have evidence arguing in favour or against this dosing strategy.

In this case our patient is already at 33 weeks gestational age, so she will require full dose anticoagulation (Dalteparin 15,000 units daily) until the delivery date, as it will be within 3 months of her PE diagnosis.

[bg_faq_end] [bg_faq_start]In the peripartum (period around delivery) period

Our patient needs a scheduled delivery date (either induction of labour or planned caesarean section) because she needs anticoagulation until her delivery date.

Setting a specific time is important as it will allow us to stop her anticoagulation with enough time to minimize bleeding risk (from delivery) and allow for epidural anesthesia if she desires. LMWH should be discontinued at least 24 hours before induction of labour and neuraxial anesthesia 5.

Her obstetrician sets a specific date for an induced vaginal delivery. She has been taking her Dalteparin at night so you ask her to take her last dose the evening 2 days before her induction date. This ensures she has had at least 24 hours off of anticoagulation before her expected epidural insertion time.

[bg_faq_end] [bg_faq_start]Postpartum anticoagulant management

Patients with VTE during pregnancy require at least 6 weeks of anticoagulation postpartum, as the postpartum period is the highest risk for recurrent thrombosis.

The day after her delivery, you arrive to find mother and baby doing well. After congratulating your patient and admiring her new infant, you explain to her that you’ll need to resume her anticoagulation. You prescribe Dalteparin 5,000 units beginning the morning after her delivery (post-delivery day 1). The next day there are no concerns about bleeding so you increase her back to a full dose of 15,000 units daily (post-delivery day 2).

[bg_faq_end]In women who are breastfeeding, there are two options for postpartum anticoagulation:

- Warfarin – unlike DOACs, Warfarin has proven to be safe for breastfed infants. Keep in mind that getting out of the home for INR checks with a newborn can be challenging!

- LMWH – safe during breastfeeding

After discussion, the patient discloses she intends to breastfeed her new baby, and she elects to continue LMWH for convenience purposes. Before you go, you reaffirm the danger signs, arrange for follow-up, and wish her luck.

Case Conclusion

You see her in follow-up six weeks after the delivery. Mother and baby are doing great, and they are thankful for all your help during pregnancy.

She has been self-injecting the LMWH for six weeks, and you ask her to stop the injections at this point.

Given that her VTE occurred in association with estrogen/pregnancy, you advise that she should avoid estrogen-containing oral contraceptives in the future, and that progestin-only methods would be safer. You also advise that if she becomes pregnant again in the future she should be seen again for consideration of antepartum and postpartum VTE prophylaxis 5.

Main Messages

- LMWH is the antithrombotic therapy of choice in pregnancy for acute VTE as it is safe for the developing fetus, and carries a lower risk of bleeding than UFH

- Care of the pregnant patient with acute VTE must be coordinated with an interdisciplinary team which includes Obstetrics and Anesthesia

- A minimum of 6 weeks of postpartum antithrombotic therapy is required as the risk of recurrent estrogen-associated VTE is highest in this time period

All the content from the Blood & Clots series can be found here.

This post was reviewed by Mark Woodcroft, Teresa Chan and copyedited by Rebecca Dang. Infographic content was reviewed by Dr. Deborah Siegal, McMaster University.