The intoxicated patient is commonplace in the Emergency Department (ED), typically there is little clinical concern with these patients, and they are set up for the “breakfast plan”; to discharge them home once they are conversing and ambulating normally. These patients, however, have the potential to have significant alcohol related diseases are often under-diagnosed and under-recognized, and we seek to discuss when the ED physician should investigate these patients further.

Alcoholic Ketoacidosis

Alcoholic ketoacidosis (AKA) is typically under-recognized in the ED, but can have significant morbidity and mortality associated with it. It is estimated that 7-10% of sudden deaths in chronic alcoholics are attributed to AKA [1].

From a pathophysiologic standpoint [2,3]:

- Ketone bodies form from the liver as a result of low insulin and high glucagon levels (i.e.: typically as a result of hypoglycemia or starvation).

- Ketone bodies are ultimately used by multiple tissues as an energy source when there is limited glucose available.

- AKA occurs as a result of significant EtOH consumption and malnutrition requiring increased body glycogen utilization.

- EtOH is converted to acetaldehyde by alcohol dehydrogenase, resulting in high levels of NADH.

- NADH impairs gluconeogenesis and results in enhanced free fatty acid formation.

- Following a binge, or during illness – catecholamines surge, and the resulting enhanced glucagon secretion results in further free acid conversion to ketones.

- These ketones result in the creation of a high anion gap metabolic acidosis, which is worsened by the enhanced pyruvate to lactate conversion noted with elevated circulating NADH.

- Additionally, these patients tend to be volume deplete, which results in decreased renal elimination of acetoacetate and beta-hydroxybutyrate, which therefore contributes to worsening of the acidosis.

Presentation

- Typical presentation is noted in chronic alcoholics, with a background of malnutrition, recently having had a binge, develop some abdominal pain, and as a result they cease drinking. It is unlikely that these patients will develop AKA while currently binging or intoxicated, as EtOH will act as an caloric substrate.

- Once they’ve stopped drinking they may develop the alcoholic acidosis, resulting in nausea and vomiting.

- This entire clinical picture is worsened by an element of starvation ketosis that is typically seen in chronic alcoholism.

- Patients may endorse a previous history of similar symptoms, as the most common risk factor is a previous history of AKA.

On physical exam, they tend to be tachycardic, tachypnic and may be hypotensive. They have non-focal abdominal tenderness and may have an altered level of consciousness [2,3].

Investigations

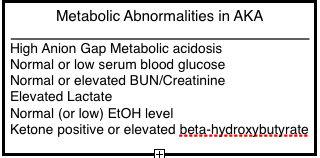

The diagnosis of AKA should be considered in chronic alcoholics with the primary complaint of abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. Their presentation may mimic that of pancreatitis or sepsis, and so in addition to routine blood work the ED physician should also investigate:

- VBG

- Lactate

- Lipase, LFT’s, Cr, Blood glucose

- EtOH level will typically be low or undetectable

- ß-hydroxybutyrate or serum ketones (depending on what your shop is currently using)

- ß-hydroxybutyrate is considered to have a higher sensitivity compared to serum ketones

Ultimately; ketones or an elevated ß-hydroxybutyrate are not necessary for the diagnosis, but help to confirm the diagnosis if present.

In the patient with abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, with a high anion gap metabolic acidosis, the diagnosis of AKA should strongly be considered.

It is differentiated from diabetic ketoacidosis on clinical grounds, and the glucose is particularly useful, as it is not usually elevated in AKA.

Treatment

These patients will typically require admission to hospital for management of their acid-base status, and inevitable withdrawal symptoms [2,3].

Initial ED management:

- Fluid hydration: utilizing D5W as your replacement fluid.

- Dextrose will help increase insulin secretion, which will minimize ketone production and enhance ketone utilization.

- It was previously thought that thiamine needed to be given prior to glucose to mitigate the risk of Wernicke’s encephalopathy, but this has not yet been borne out clinically or in the literature [3].

- Previous studies have demonstrated that providing only normal saline may worsen the patient’s condition by prolonging lactate clearance and enhancing the metabolic acidosis (likely due to hyperchloremia).

- Dextrose will help increase insulin secretion, which will minimize ketone production and enhance ketone utilization.

- Remainder of treatment is supportive:

- Replacing electrolyte losses; particularly hypokalemia, hypomagnasemia, hypophosphatemia and hypoglycemia.

- Benzodiazepines to minimize inevitable alcohol withdrawal symptoms.

- Thiamine/Folate replacement (see below for further details on dosing).

- It is important to rule out other causes for the patient’s presentation, such as sepsis and serious abdominal pathology.

Wernicke’s and Korsakoff Syndromes

It is important to remember that Wernicke’s and Korsakoff’s are two pathophysiologically similar, but clinically different entities.

Wernicke’s Encephalopathy

Wernicke’s (WE) is primarily a clinical diagnosis, with an estimated prevalence of 12% in patients with an alcohol use disorder, with an associated mortality of 20%. However, this is likely an under-representation, as autopsy studies have suggested a higher rate of Wernicke’s than estimated by clinical data [4].

Wernicke’s occurs as a result of Thiamine (Vitamin B1) deficiency, due to chronic malnutrition, impaired GI absorption, diminished hepatic storage and utilization.

Diagnosis is baed upon the Caine criteria: (requires >2 features, sensitivity approaches 100% in chronic EtOH users) [5,6]:

- Nutritional deficiency

- Altered level of consciousness

- Oculomotor abnormalities

- Typically: nystagmus, lateral rectus palsy and conjugate gaze palsy.

- Cerebellar dysfunction/ataxia

WE is a clinical diagnosis, and therefore there is little role for investigations in the ED, except to rule out other potential etiologies for the patient’s presentation. MRI may help to identify cranial lesions to support the diagnosis, but this should not be performed in the ED.

Treatment

Since WE has significant potential morbidity and mortality, treatment should be initiated once clinical suspicion has been established. Thiamine is safe and well tolerated, while anaphylaxis and bronchospasm are documented side effects, these are increasingly rare.

The dose of thiamine has some controversies associated with it, as it is not well studied. However, consensus guidelines and expert opinion recommends starting with a dose of Thiamine 500 mg IV (over 30 minutes) q8h for two days, then 250 mg IV once daily for 5 days, followed by 100 mg po once daily. Patients who are at risk, or have a clinical concern for WE are at risk for malabsorption, which is why the oral route is not recommended during initial replacement [7].

Most patients tend to have improvement in their ocular symptoms within hours to days, cerebellar findings can take weeks to correct and confusion improves within days to weeks.

Korsakoff Syndrome

Korsakoff Syndrome (KS) exists as the end stage manifestation of Wernicke’s encephalopathy, and as a result occurs via the same pathophysiologic mechanism as WE.

The diagnosis is once again made in the setting of chronic alcoholism, and is taken from the DSM-IV [9,10].

- One of either anterograde or retrograde amnesia

- One additional cognitive symptom:

- Aphasia

- Apraxia

- Agnosia

- Abnormalities in executive functioning: confabulation and apathy are often common manifestations of this, but are not a diagnostic requirement.

- The memory impairment must represent a decline from previous functioning, and impair with the ability to perform normal activities, with other medical problems having been ruled out.

Unfortunately, there are few treatment options available for Korsakoff syndrome and most patients eventually require long term care placement, as they are unable to care for themselves or function independently.

Vitamin B12 / Folate Deficiency

Chronic alcoholics are at increased risk of vitamin B12 and folate deficiency secondary to malnutrition, and previously discussed effects of EtOH on GI motility, absorption and enzymatic utilization.

B12 Deficiency

Vitamin B12 is found in animal products (meat and dairy), and body stores are typically high (hepatic), so a purely dietary B12 deficiency is quite rare, and can take years to clinically manifest [11].

“Classic Triad”:

- Weakness

- Parathesia

- Sore tongue

Patients may also demonstrate:

- Megaloblastic anemia

- Neurological changes:

- Symmetric polyneuropathy: legs > arms

- Ascending parathesia

- Loss of proprioception

- Can progress to weakness, spasticity, clonus, paraplegia and loss of bowel/bladder function.

- Memory loss, cerebellar ataxia and extrapyramidal side effects may develop later in the disease.

- Increased osteoporosis risk

Causes of B12 Deficiency:

- Inadequate dietary intake (total vegetarianism, chronic alcoholism).

- Inadequate absorption:

- Absent/ineffective intrinsic factor (pernicious anemia, H. Pylori).

- Pernicious anemia: autoimmune disorder resulting in destruction of parietal cells and gastric intrinsic factor, causing decreased cobalamin absorption (most common cause of B12 deficiency).

- Abnormal ilium (i.e.: IBD).

- Inadequate use:

- Enzyme deficiency

- Abnormal vitamin B12 binding protein

- Increased requirement by increased body metabolism: HIV, hemolysis, pregnancy.

- Increased excretion or destruction

Workup

- B12 deficiency should be considered and investigated in those presenting with unexplained ataxia, polyneuropathy or parathesia, particularily in the malnourished or chronic alcoholic.

- B12 levels may be readily obtained in most laboratories.

Treatment

- B12 replacement; responds well to therapy.

- Should be given IM initially, as malabsorption is common in this patient population.

Folate deficiency

Folate is typically found in animal products and leafy vegetables.

An important distinguishing feature between folate and B12 deficiency is that a folate deficiency will not cause neurological symptoms, which is a signfiicant hallmark of B12. Timing is another important factor, as typically B12 will take years to manifest (as body stores are high), while folate stores are lower, so a deficiency may manifest within months.

The presentation of folate deficiency is vastly different than that of B12, with many non-specific symptoms manifested. Patients may complain of persistent fatigue and lethargy, depression and increased irritability. Hematologically, they will typically demonstrate a megaloblastic anemia, and their folate levels will be low.

Causes of folate deficiency:

- Inappropriate intake

- Substance abuse/chronic EtOH abuse

- Malnutrition

- Overcooked foods

- Inadequate absorption

- Celiac disease

- IBD

- Infiltrative bowel disease

- Short bowel syndrome

- Drugs

- Methotraxate

- Trimethoprim

- EtOH

- Phenytoin

- Increased requirements

- Pregnancy

- Chronic hemolysis

- Hereditary folate malabsorption

Treatment

Folate replacement may be done orally in the ED with 5 mg po. This may be extended in the outpatient setting to 1-5 mg po daily for one-four months, trending hematologic studies to further evaluate for improvement.

[bg_faq_start]References

- Komáreková I, Janík M. Ethanol-induced ketoacidosis as a possible neglected cause of sudden death in chronic alcohol consumers. Soud Lek. 2014; 59(4):48-50. PMID: 25417642

- Allison MG, McCurdy MT. Alcoholic metabolic emergencies. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2014; 32(2):293-301. PMID: 24766933

- Schabelman E, Kuo D. Glucose before thiamine for Wernicke encephalopathy: a literature review. J Emerg Med. 2012; 42(4):488-94. PMID: 22104258

- McGuire LC, Cruickshank AM, Munro PT. Alcoholic ketoacidosis. Emerg Med J. 2006; 23(6):417-20. PMID: 16714496

- Isenberg-Grzeda E, Kutner HE, Nicolson SE. Wernicke-Korsakoff-syndrome: under-recognized and under-treated. Psychosomatics. 2012; 53(6):507-16. PMID: 23157990

- Day GS, del Campo CM. Wernicke encephalopathy: a medical emergency. CMAJ. 2014; 186(8):E295. PMID: 24016788

- Kim TE, Lee EJ, Young JB, Shin DJ, Kim JH. Wernicke encephalopathy and ethanol-related syndromes. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2014; 35(2):85-96. PMID: 24745886

- Latt N, Dore G. Thiamine in the treatment of Wernicke encephalopathy in patients with alcohol use disorders. Intern Med J. 2014; 44(9):911-5. PMID: 25201422

- Levy WJ. Transcranial stimulation of the motor cortex to produce motor-evoked potentials. Med Instrum. 1987; 21(5):248-54. PMID: 3683251

- Kopelman MD, Thomson AD, Guerrini I, Marshall EJ. The Korsakoff syndrome: clinical aspects, psychology and treatment. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009; 44(2):148-54. PMID: 19151162

- Fragasso A, Mannarella C, Ciancio A, Sacco A. Functional vitamin B12 deficiency in alcoholics: an intriguing finding in a retrospective study of megaloblastic anemic patients. Eur J Intern Med. 2010; 21(2):97-100. PMID: 20206879