Ok, I’ll concede that title is pretty bad, but I felt my usual name for Tramadol (Tramacrap), just didn’t seem as appropriate for a headline. Dad jokes aside, Tramadol is a synthetic opioid that entered the Canadian market in 2005, and has seen widespread uptake and use. Unfortunately, Tramadol has not been the miracle drug that we anticipated it would be, as is fraught with harms. Alarmingly, despite a host of problems associated with this medication (as we will get in to), the Canadian government has yet to reclassify Tramadol as an opioid, and this has some concerning ramifications.

What is Tramadol?

Tramadol is a synthetic analgesic that is converted to M1 (an opioid) by the liver, as well as enhancing serotonin and norepinephrine neurotransmission – resulting in its dual action analgesic properties1. The problem, however, is that the metabolism of tramadol varies significantly for individual patients (very similarly to codeine), and so in the vast majority of patients, the analgesic response can be unpredictable, so it is hard to know exactly how much ‘analgesia’ any individual person is receiving. The metabolism of tramadol occurs via the cytochrome P450 system, and as a result a wide array of drug interactions can also alter the pharmacodynamics and effects of this medication1.

Tramadol dependence and withdrawal

Since Tramadol is considered an synthetic opioid, one of the initial marketing components was that it caries significantly less risk of dependence and withdrawal compared to more typical narcotic analgesics. However, as increasing number of patients are now taking this medication, we’re discovering more data and evidence to suggest this original claim is not true.

Evidence is emerging that large numbers of patients will experience physiological dependence on Tramadol, and will have unpleasant withdrawal symptoms when the drug is stopped. The majority of patients chronically taking Tramadol will experience a typical opiate withdrawal syndrome. However, around 1/8 patients will experience some atypical withdrawal symptoms, including anxiety, panic attacks, insomnia, hallucinations, confusion, paranoia, and unusual sensory changes2. Alarmingly, this dependence occurs both in individuals with a history or risk factors for opioid abuse, but as well in those with no history of substance abuse3. As a result of more emerging cases of dependence and withdrawal, patients and physicians are becoming aware to this phenomenon, however, we’re not often cognizant of this when starting patients on this medication.

Toxic Effects

Even though it is technically an synthetic opioid, given its variable metabolism – it is hard to predict what patient’s will experience. As a result, patient’s may experience an opioid toxidrome secondary to the use of Tramadol. This is certainly demonstrated by case reports of morbidity and mortality secondary to apnea. Most typically, this occurs at high doses (usually intentional), however, there are reports of apnea at lower doses as well as accidental overdoses4. While the opioid component of this toxidrome responds appropriately to Narcan (note, that the drug effect is only partially treated with Narcan), many of these patients would not have narcan at home, nor consider its use – as Tramadol is sold and marketed as a ‘safe’ opioid alternative, and is not classified as a controlled substance by Health Canada.

Another concerning toxicity that we may see with Tramadol use is serotonin syndrome. One of the mechanisms of Tramadol enhances serotonergic activity, and when patients are also taking SSRIs (or other serotonin based medications), this effect is significantly compounded. SSRI’s act as P450 inhibitors, increasing drug concentrations, and enhance the risk of drug toxicity or serotonin syndrome even further5.

Tramadol has also been implicated in spontaneous seizures in patient’s abusing this medication. It appears that this risk is compounded by substances or medications that may alter seizure threshold6. The evidence would suggest that the seizures occur as a result of neurotoxicity, with or without elements of serotonin syndrome. A 3 year study examining this effect concluded that Tramadol should certainly be avoided in patients with epilepsy, or taking SSRIs, TCA’s or antipsychotics6.

Scheduling in Canada

Unfortunately, Tramadol is currently not a controlled medication in Canada (even though the FDA in the United States made this change in 2014). Health Canada had looked into changing the classification in 2007, but after meeting with the drug manufacturers this plan was abandoned. While the scheduling of Tramadol as a controlled substance seems mostly semantic, this would herald an important change, as it would help to reduce the inappropriate stigma that Tramadol is a ‘safe alternative’ to opioids, and would appropriately classify it as an potentially harmful medication for physicians and patients.

Conclusions

We’re in the midst of an opioid crisis, with increased emphasis on opioid prescribing and the utilization of alternative or adjunctive medications. The emerging evidence against Tramadol should deter us from reaching for this medication as an alternative. While we should be mindful of prescribing opioids in general, Tramadol likely should not be a first line agent for patients, and we need to be very careful prescribing this medication for those who are already on serotonergic agents. Health Canada is apparently looking into the scheduling of this medication, and that would go a long way to increasing awareness about the harms of Tramadol.

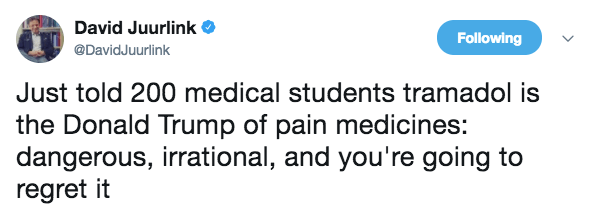

Perhaps the best summation of Tramadol comes from Canadian toxicologist and expert, Dr. David Juurlink: